The legendarily wronged Apache Kid (includes exclusive chapter)

'Quintus Hopper of Nevada' series: In the history of the Wild West, newspapers did everything they could to demonize American Indians, by distorting, embellishing and outrageously lying.

Quintus Hopper of Nevada, published in January 2022, is a historical novel that follows the epic and peculiar life of a frontier newspaper typesetter. As part of my research, I made extensive use of newspaper archives and, in this series, I’ll share some of my often-surprising findings. Here are history, commentaries and contemporary newspaper articles as they relate to my latest novel. This time, a look at the Apache Kid. Here’s a perfect example to illustrate how, beyond outright slaughter, constant lies by white men about American Indians caused tremendous harm. The Apache Kid, if anything, shouldn’t just get an apology, but a medal for bravery and persistence against seemingly insurmountable odds.

The novel ‘Quintus Hopper of Nevada’ gives a particular focus to another supposed American Indian villain - the infamous Queho, in Southern Nevada. In addition, it also tells the story of Ahvote and of Willie Boy (in California). The case of the ‘Apache Kid’ was part of an earlier draft, but didn’t make it to final manuscript. I’d still like to include it here as the article in the Los Angeles Herald illustrates white man’s storytelling bias quite clearly – as the article says: ‘A more cruel, cowardly villain of the Apache tribe, or any other tribe or aborigine race for that matter, would be difficult to find.’

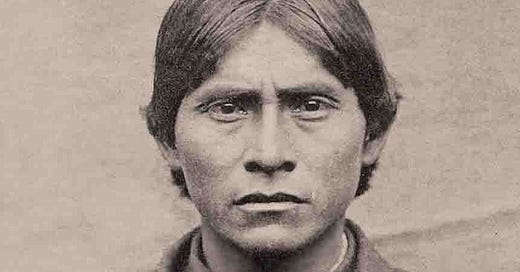

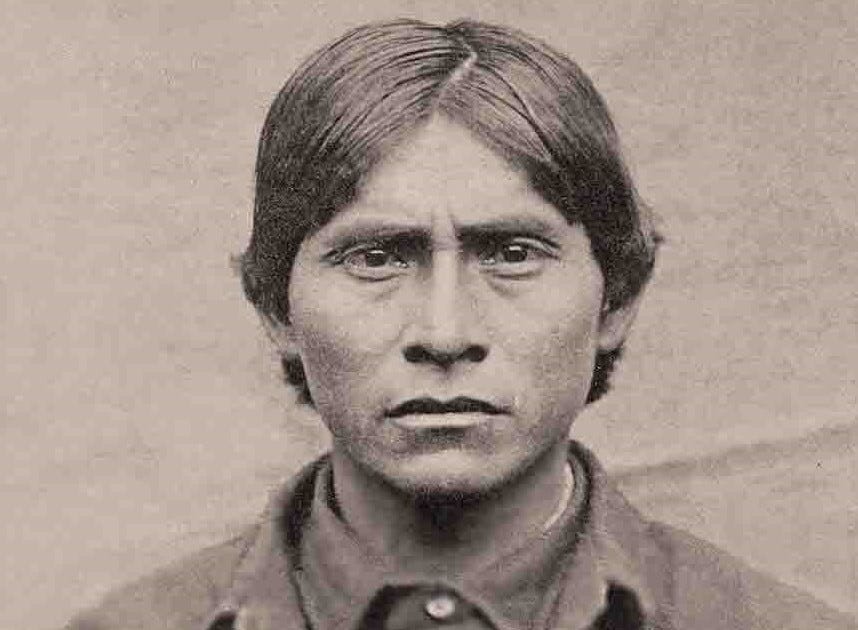

The Apache Kid was none of what the papers made him out to be, even if he had killed. His real name, Haskay-bay-nay-ntayl, had been too much of a verbal challenge for the white men of Globe, on the San Carlos reservation, and so they began calling him the Apache Kid, often simply the Kid. The meaning of the boy’s real name, ‘brave and tall and will come to a mysterious end,’ was known to none of the whites – but they did notice that the young boy, smart, handsome and soft-spoken, stood out from the pack of the other youths. A quick learner, he soon spoke English, and at the age of fifteen was a first-rate wrangler and marksman. It was there he met Albert Sieber, the man who would, for good and ill, shape his life.

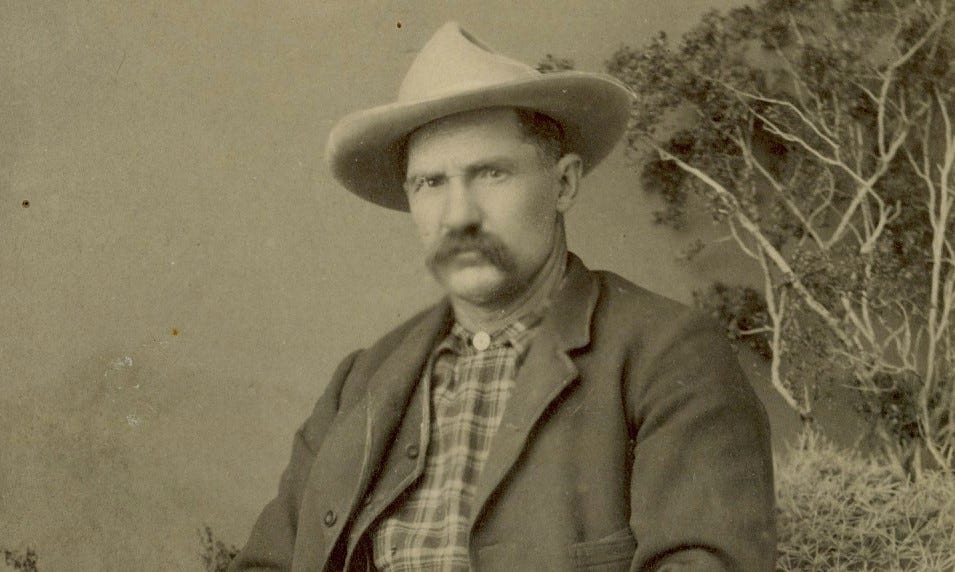

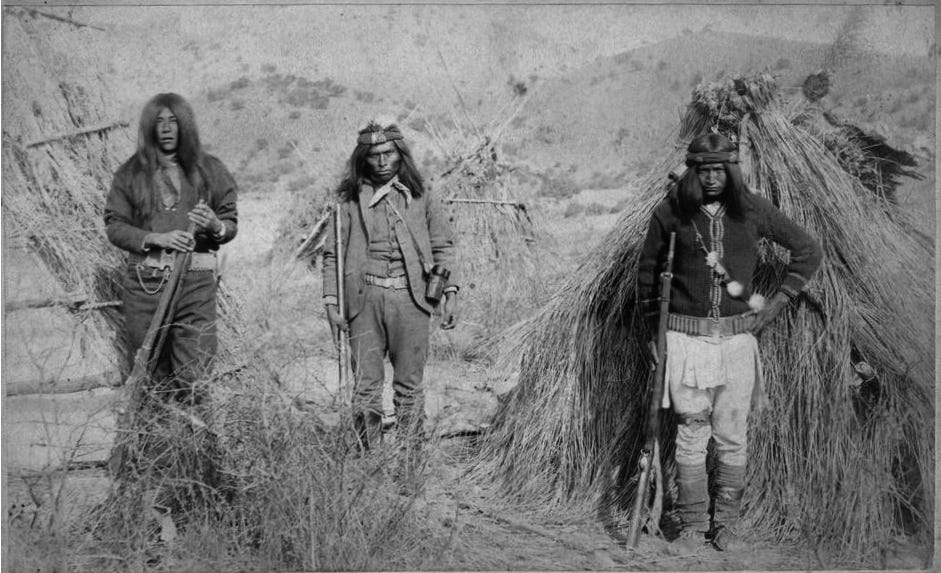

Sieber was Chief of Scouts for the U.S. Army in the Apache wars and he took the young boy under his wing. The army had long recognized that, if they fought the old way, they didn’t stand a chance against Apache warriors such as Cochise, Victorio and Geronimo. Sieber’s scouts were Apache, and their tracking abilities and local intelligence were invaluable. By 1881, Sieber enlisted the Kid with the U.S. Cavalry as a scout – and just one year later the young Apache was commended for his abilities with a promotion to sergeant. The Kid was with General Crook, and later with General Miles, tracking and hunting down Apache outlaws. And by 1887 he was established as Al Sieber’s second in command.

May of that year, Sieber and several Army officers were called away and Sieber left the Kid in charge of the scouts at the San Carlos post. When one scout killed the Kid’s father, the Kid evened the score. He also killed the man who had instigated the murder of his father. It was justified, it was the Apache way. When Sieber and the officers returned, they ordered the scouts involved in the murders to surrender their weapons. The Kid was the first to comply with his mentor’s request. He would not resist arrest and instead would patiently await the findings of the army’s investigation of the incident. On the first of June, 1887, when the Kid laid his weapon onto the table, the other accused scouts followed suit. When a gun went off, shattering Sieber’s ankle, mayhem followed. When the dust settled, the Kid and several other Apache had vanished. However, the Apache Kid returned two weeks later, ready to face the consequences of his actions. He had not shot Sieber, as was affirmed by a number of witnesses, all he had done was to avenge the murder of his father. Surely the U.S. Army, his employer, and Al Sieber, his mentor, would see that he had not wronged anyone.

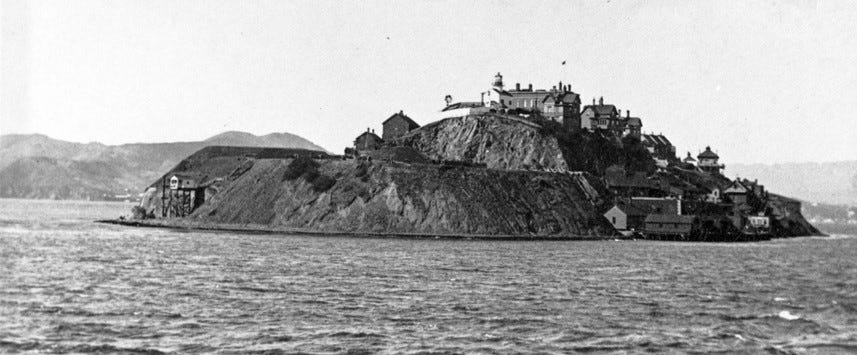

He did not know that the army had decided to make an example of him. The Kid and four others were court martialed with mutiny and desertion and condemned to death by firing squad. After General Miles himself intervened and reduced the sentence to ten years, the scouts were sent to Alcatraz to serve their sentence.

The Kid survived month after month in the military prison, a hellhole of violence and disease. To everyone’s surprise the conviction was overturned after ten months and he was set free. When he returned to Arizona with a clean record, the white men at Globe were having none of it. They realized that there was nothing they could do about the reversed verdict of the court martial, and so decided to bring a civil charge. They accused the Apache Kid and three others of the attempted murder of Al Sieber. Sieber himself testified that the Apache Kid had shot him. The Kid was convicted once more, this time the punishment was a seven-year prison sentence at Yuma Territorial Prison… the Kid would never see the inside of that prison, or any other.

He was among the nine prisoners in the transport wagon, watched by a sheriff, a guard and the driver. When the trail was too steep for the horses, seven of the prisoners were ordered to walk. Only the Kid and one other scout remained shackled in the wagon, and from there they saw the other prisoners attack the lawmen. Within moments, guns had been taken, the sheriff and guard shot and killed, and the Apache Kid released. One of the prisoners was about to kill the driver with a rock, but was stopped by the Kid. The driver eventually made it back to town, told what had occurred, and that the Apache Kid had saved his life.

Al Sieber himself set his scouts on the trail of the escaped prisoners. One by one, they were caught, killed or captured. The Apache Kid, however, remained out there, a looming presence. He was thirty years old by then, but the name remained, the Apache Kid – and every death, murder, raid, robbery and kidnapping were laid at his feet. Over the years many claimed to have slain him, but no one was ever able to collect the large bounty that had been placed on the Apache Kid, dead or alive.

September 13, 1894

Los Angeles Herald, Los Angeles

KID, THE WILD APACHE.

HE IS SAID TO HAVE KILLED ANOTHER COWBOY.

The Wild Indian Followed Only by a Squaw, the Others Having Deserted Him – His Bloodthirsty Nature.

“Apache Kid,” that young Arizona aborigine who has been woven in and out of more wild west romances – in the newspapers – than any other character who has occupied public attention in and out of the territory since the days when Geronimo went stalking about with General Miles’ trailers on a hot scent, is again accused of murder.

The Arizona Citizen of Sunday contains an account of the murder of a cowboy some 20 miles from Tucson, and as no one else seems responsible, it is laid to the door of Kid the Apache. One or two, more or less, don’t count very much, and the Kid can probably stand the imputations without hurting his feelings.

Capt. Dick Falkenburg, the Arizona scout, and one who is particularly well informed about the territory over which the Apache makes his haunts, tells some interesting stories about the renegade. He says that the Kid roams about in the Galluro range of mountains, which extends north from the Mexican line a distance of about 35 miles, and 50 odd miles from Tucson. For two years he has not been seen, at least not at very close range, but he knows that he is still alive. He is deserted by his former comrades in crime and his sole companion now is a squaw, whom he ran off with some time ago. The Indian is about 28 years of age and very slight in build. He will weigh about 130 pounds. In disposition he is very cowardly and treacherous, and his assaults have always been at close range, when he was pretty apt to be on the safe side.

One characteristic of his disposition is that when he tires of his squaw he kills her and goes off to San Carlos reservation and steals another. One squaw followed him in his wanderings for over two years but this has been the exception. His cruel nature extends to his horses which he may pick up. If one, after being ridden, does not suit it receives a dagger thrust in the heart. A more cruel, cowardly villain of the Apache tribe, or any other tribe or aborigine race for that matter, would be difficult to find. Captain Dick says the stories about his education are the merest nonsense.

Here the chapter that didn’t make it into the final novel. In it, the Apache Kid meets with Owl Woman after he crosses the border into Mexico. She tells him that he will never be caught, and that the white men will someday name that land after him - it is the Apache Kid Wilderness.

THEY WILL NEVER CATCH YOU

He had crossed over into a Mexico two days before, with no particular destination in mind. He knew the lands. He had tracked Geronimo and his men in and out of those mountains. Now Geronimo was an old man, and they were still keeping him away from his homeland. They had sent him to a reservation in Florida, then to Alabama – and now he was relocated once more, this time to Oklahoma. An old man, and still they were afraid of him … now I’m the outlaw, the Apache Kid thought. He exhaled, through the nose, and lightly tugged at the reins. His horse halted. Something’s wrong, the Indian thought. Someone’s watching me.

He reached for his rifle, slowly, casually leaning forward as if to simply pat the horse’s neck. The Kid’s senses were alert in every direction. There was nothing unusual, not to his eyes, not to his ears, not to his nose. The birds were singing, unafraid, undisturbed. What was he sensing? There was a rock to his left, crouched between two juniper bushes. To his right, a few trees and a trickling creek. He let go of the rifle and sat up straight once more.

“You’re a bit old for a kid,” the rock said.

The Apache Kid whirled around and there, where the rock had been, sat an old Indian woman. She was small and gnarly, wrapped in a rabbit-skin cloak – and she smiled up at him.

“Who are you?” the Kid asked.

“You know who I am.”

The Indian looked at her for a moment, then jumped off his horse. As the animal trotted off to find a good grazing spot, the Apache Kid, after scanning the surroundings, sat down next to the old woman. He crossed his legs and looked into her eyes.

“I have heard of you,” he finally said.

“Did you know that you committed a murder near Mount Reno a few days ago?”

“I wasn’t anywhere near Mount Reno a few days ago.”

“I know that. You know that. Yet they’re still hunting you.”

“They won’t catch me.”

“They won’t catch you,” she agreed.

“… Ever?” he asked.

“They will never catch you.”

“Why are you here, Owl Woman?”

She gave a light shrug, and then she smiled.

“Why do you think?”

“… I don’t know.”

“I like stories,” she said. “And I like people … well, some people. And I am glad to meet you.”

“As am I,” the Indian said.

“They will declare you dead in a few days. And they will declare you dead many more times.”

After a moment, she chuckled.

“What it is it?” the Apache Kid asked.

“One time they’ll kill you and then they’ll name a mountain after you.”

“Where?”

“New Mexico Territory – they’ll call it the Apache Kid Peak.”

He lightly shook his head, frowning. So much had happened. So much, so wrong … so vile. Al Sieber had been his friend, or so he had always thought. The Kid would remain in Mexico for the rest of his life, a long life, well lived, in peace and in love. Despite everything, he would always think of Al Sieber as a friend. And had he known that Al Sieber, the man who had survived countless battles, would be buried and killed in 1907 by rolling rock, the Apache Kid would have been sorry to hear it.

The Kid realized that he felt warm, at ease, at home. There, somewhere in between where he had come from and where he would be, he knew himself to be at home in the company of the old woman. For the first time in years he slackened his shoulders, and in that moment, the weight of a mountain slid from his back.

“You’re free,” Owl Woman said.

The Apache Kid smiled.

Beautiful piece. I especially enjoyed the chapter that didn't make it into the novel. And I can't stop staring at the black and white photo of The Apache Kid. His eyes are so alive, and there's weltschmerz but also a stoicism in them that is hard to fathom, given the horrible injustice that was done to him and his people in general.