The Transcontinental Railroad (includes exclusive chapter)

1869 was a landmark year for frontier America. The completion of the railroad was seen as more important than the gold and silver rushes. They were right.

Quintus Hopper of Nevada, published in January 2022, is a historical novel that follows the epic and peculiar life of a frontier newspaper typesetter. As part of my research I made extensive use of newspaper archives and, in this series, I’ll share some of my often surprising findings. Here are history, commentaries and contemporary newspaper articles as they relate to my latest novel. Here a look at the coming together of the Transatlantic Railroad.

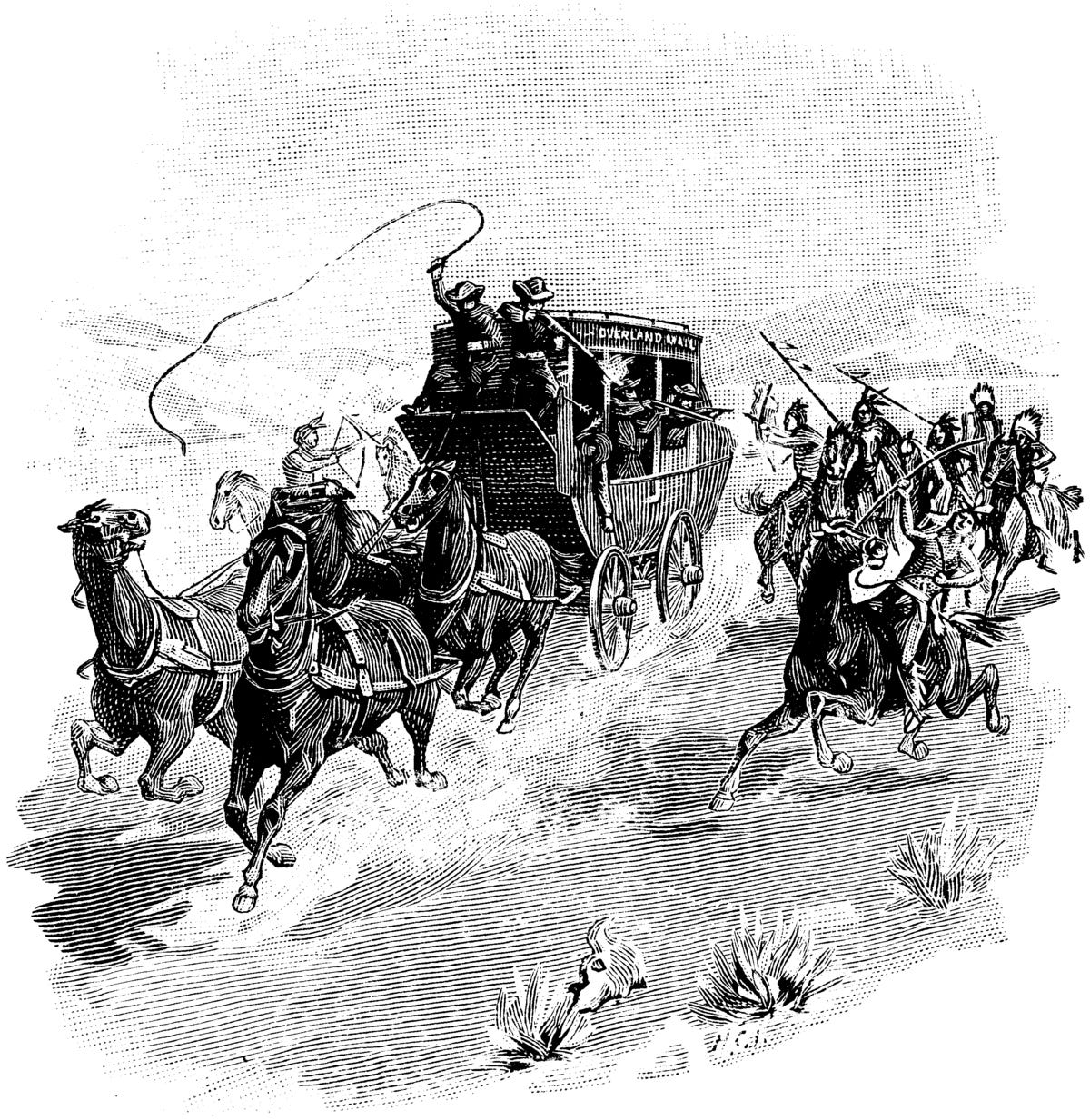

1869 was, without a doubt, a breakthrough year for the United States. In Roughing It, Mark Twain gives an excellent description of just how long and challenging a stagecoach trip was in the times before the railroad. Here’s how his journey began - a journey that brought about the creation of the man himself. Without that time so wonderful described in Roughing it, Samuel Clemens would have never become Mark Twain.

“At the end of an hour or two I was ready for the journey. Not much packing up was necessary, because we were going in the overland stage from the Missouri frontier to Nevada, and passengers were only allowed a small quantity of baggage apiece. There was no Pacific railroad in those fine times of ten or twelve years ago—not a single rail of it. I only proposed to stay in Nevada three months—I had no thought of staying longer than that. I meant to see all I could that was new and strange, and then hurry home to business. I little thought that I would not see the end of that three-month pleasure excursion for six or seven uncommonly long years!”

With the railroad, from one moment to the next, distances and time shrank and what was impossible before, soon became commonplace. The transporting of goods and people further increased and brought ever more white people to look for and claim new homes in Indian lands. The below editorial in the Carson City's Daily Appeal gives a great example of the glowing fervor that spread across the lands with the coming of the railroad.

In the novel, Quintus works on the railroad for a while and meets, and makes friends with, a great Irish storyteller. Below two things - the newspaper article and a chapter that didn’t make it into the final book. It’s is one where Quintus stays with the railroad until the golden spike at Promontory Summit. Enjoy!

May 11, 1869

The Daily Appeal, Carson City

THE CONSUMMATE TRIUMPH

OF ENTERPRISE AND IRON.

Gold has paid its largest and best tribute to its elder and more useful brother – Iron. Marshall, who found the first nuggets at Sutter’s mill, has lived to see grand and triumphant vindication of his discovery. California and Nevada are no longer far off provinces of the United States; “A Pacific Empire” is no more a temptation or a possibility. As the war wiped out the cause of sectionalism between the North and the South, so has the driving of the last spike promoted the obliteration of a like feeling between the far East and the far West. Homogeneity and the final rail of the great railroad are synonymous. We of Carson can, by traveling thirty miles (to Reno) look at cars and locomotives that have come from Maine to prove that this is still one country, united by the continuity of a common soil and common interests. The six months voyage of the ox team is superseded, forever, by the four days’ journey of the iron horse. The emigrant trail is brush-grown and forgotten; and the Truckee is but an incident of a pleasure trip, not the camping ground of the weary pilgrim searching for the promised land. Women and children with posies and cakes from the gardens and kitchens of our neighbor, Chicago, may be seen by anybody who will go hence to the side stations of the long track. The old civilization has come upon us with its home emblems is its hands. Wholesale and utter revolution has come upon us at once; and we are no more isolated and set apart. We shall be absorbed into the commonwealth of Americanism. We can get new shoestrings from Boston easier and quicker now than the men of Ormsby’s command could get succor and reinforcements from California. We are nearer Eastport than Col. Curry was to San Francisco when he and Gould located that famous mine.

“California has revolutionized the world.” Such is the hackneyed axiom. We come to understand it. We come to comprehend how it is that gold is valueless compared with iron; end yet, we are also given to understand how much gold and iron owe one another – how mutually dependent they are. The best use that the gold and silver of these parts has been to is the great railroad building. The exchange has proven that the iron is the better metal to own. But we must never forget that the precious ores have come into their noblest uses.

Carson was yesterday connected (by the telegraph wire) with London. This inconsequential little sagebrush settlement got its full share of the news quite as soon as the British Capitol got it. The strokes of the hammer which drove the spoke which fastened the rail which completes the road which binds forever and for aye the destinies and common interests of the Great Republic sounded here as it sounded on Wall street, and on Montgomery street, and, going under the seas, beneath the track of the old Mayflower, sounded within the walls of the Bank of England. Louis Napoleon and all the crowned heads of Europe got this news within half an hour from the time that it came to our ears. Talk of the age of iron! When was it if it is not now?

Here a part of an earlier manuscript - it didn’t make it into the final novel, but might be of particular interest on the subject. Here, Quintus finds himself at Promontory Summit in the very center of the action, with Leland Stanford, President of the Central Pacific Railroad, asking him to accomplish the final connecting of the transcontinental railroad:

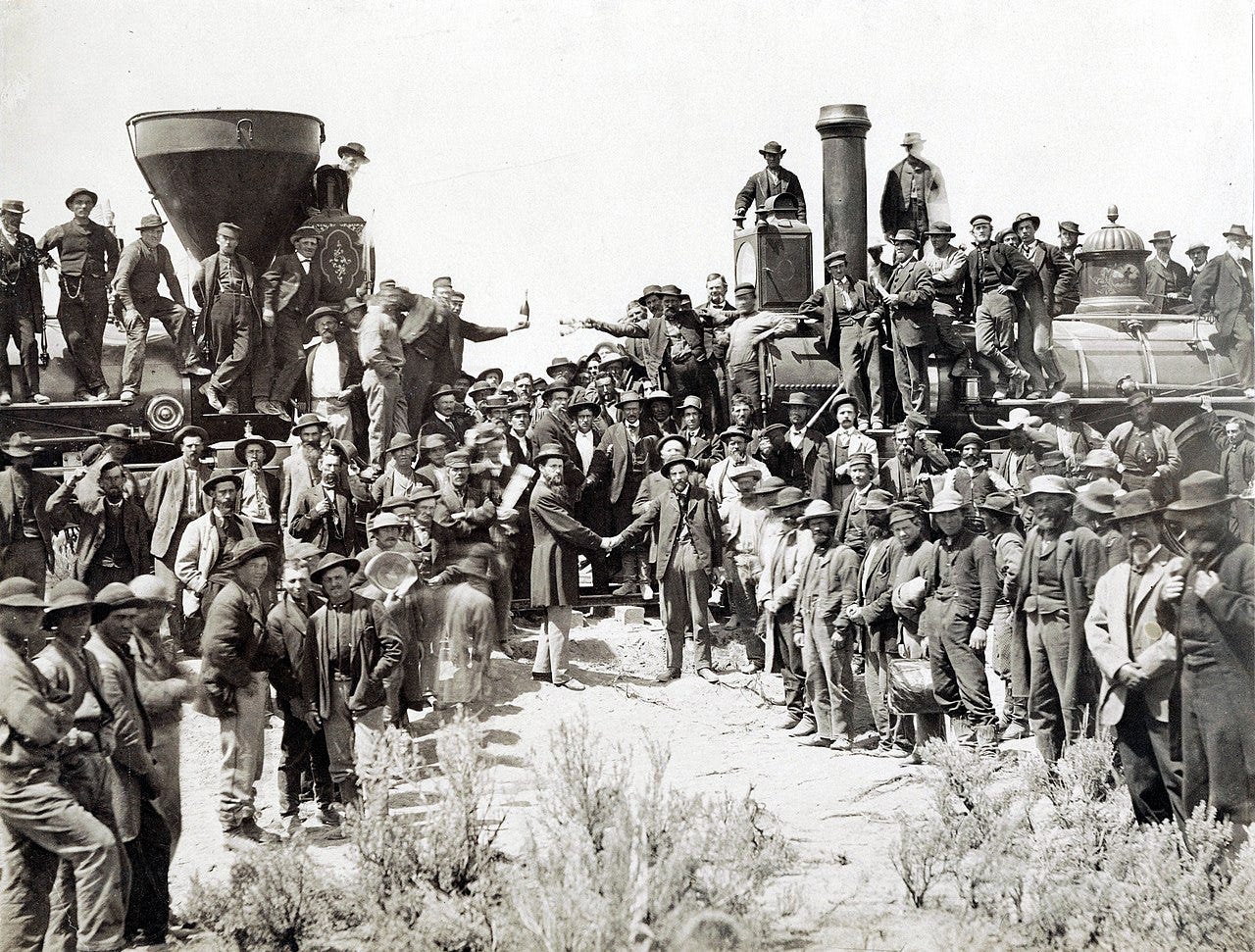

Seventeen tents. Eating houses, saloons and accommodations for the guests, the reporters, the photographers and telegraphers. Many more tents for the crews from either side of the continent. The two sets of rails met at Promontory Summit, Utah, and they had been told that the big celebration would take place on the 10th of May. Quintus had been among the Irish crews and, with the race to the finish line, they had worked hand in hand with the Chinese crews to get there in time.

Quintus stood on the spot where they’d all gather in a few hours. The rails were laid, a final ceremonial tie made of laurel wood would soon be placed in the one remaining empty space and the important men would tap in the special spikes. What was to be joined at that place would forever change the United States of America. They couldn’t have picked a more desolate place, Quintus thought. He slowly turned, eyes open, breathing deeply. He looked in every direction. Telegraphers were up on their poles to ensure all was set. Graders were adding final touches. Foremen yelled and urged and laughed. The crews had been celebrating ever since they knew they’d make it in time. Hardly any of the men had been part of the operation from the start. It had been hard work, bone- and spirit-breaking work. Many had quit, many had died. Tom Byrne, one of the few who had been there from the start, was cheered by one and all. The Irish commended the Chinese, the Chinese commended the Irish. The foremen were at ease, finally, finally. Trains arrived, bringing dignitaries and spectators – and by the time the ceremony began, with the sun high in the clear sky, more than a thousand people had gathered to witness the moment. To cheer and applaud, to clap on shoulders, to embrace, to be able to one day tell their grandchildren that “I was there.”

There were too many people. Most of them never caught a glimpse of what happened. They might have caught an occasional word, carried by the wind, of the prayers and the speeches. Quintus, a head taller than most, found himself standing near the Jupiter, the locomotive that had brought Leland Stanford, President of the Central Pacific Railroad. He didn’t listen to the words. They were what they were, expected. Instead he let his eyes roam and found himself studying the faces of the spectators, the rich, the poor and everything in between. Women in their Sunday dresses stood next to Chinese workers. Lawyers and county officials were shoulder to shoulder with men who had never entered an office. There were dignified elders and children, hushed by their parents. That moment, it remained with Quintus. It was an instant that, like a strong perfume, reached and affected one and all. There was a remarkable sense of … union.

There had also been Indians working for the Central Pacific. If there were there now, Quintus didn’t see them. And why would they be there? There was nothing to celebrate. Nothing good would come with the Iron Horse. Not for the tribes. Nothing would be bettered. Suddenly, Quintus felt the urge to leave. He didn’t need to be there, he needed to walk again. He began to gently push his way through the crowd, when a booming voice stopped him.

“You!”

Quintus turned and saw Leland Stanford, pointing at him with the spike maul in his hand. The man was imposing, his call commanding.

“Yes, you,” Stanford boomed. “Come here, young man.”

Reluctantly, Quintus made his way to the center of the crowd. There stood Leland Stanford, his arm outstretched, offering Quintus the maul. Next to Stanford stood Thomas Durant, the Vice President of the Union Pacific. He looked the opposite of Stanford, sunken cheeks, thinner, older, weaker. His bloodshot eyes also suggested that he hadn’t slept. Quintus didn’t take the maul and Stanford kept the heavy tool in place, arm straight out, unbending, knuckles tight. When he spoke, he did so as if he were experiencing no strain. He smiled, but there was no smile in his eyes.

“Take it,” Stanford said.

After a moment, Quintus took hold of the maul and Stanford, with a deep breath, shook his arm and lowered it. Quintus looked from Leland to Durant, to the tie below him. The laurel wood tie had been replaced with a proper tie. The gold and silver spikes had been taken away, the ceremony was over. It was now time to actually complete the task. Four iron spikes were waiting – and Quintus noticed that attempts had been made, the maul had left a mark in the tie, and another attempt had not even managed to hit it. As Quintus found out later, both Leland and Durant had tried, and failed, to hammer in the spikes.

“Get the job done, son,” Leland said, his voice rumbling.

Time stood still. Nothing moved, not Leland’s chest, not the flag on the pole. Quintus heard nothing but the sound of his own breathing as he wondered. Connecting the rails. It meant progress. But what’s progress, he thought. Why? Whereto? Yes, to what end? It wasn’t about good or bad, it was simply about more. More of everything. He realized that he wanted nothing to do with it. He also realized that it didn’t matter. Worlds. Worlds separated. The world without, the world within. The worlds of every single person right there at Promontory Summit and everywhere else. The moment would be recorded and remembered forever, and yet it meant nothing to Quintus.

“What are you waiting for?” Leland asked, a threat just below the surface of his face. “Come on, we’re on a schedule. The future waits for no one.”

Snapping back, Quintus took one look at the two spikes that stood ready on either side of the pine tie. He wielded the maul four times, once for each of the spikes. It had happened in a flash, with force, with precision. It took a moment for the onlookers to realize that it had been done. When they did, thunderous applause erupted. Quintus handed the maul back to Stanford and, without noticing any of the jubilations, waded through the crowd and vanished.