The perilous lives of frontier newspapermen (includes exclusive chapter)

Frontier newspapering was dangerous – quite a few newspapermen died by violent means and most of them, as they went about their work, had a revolver in easy reach.

Quintus Hopper of Nevada, published in January 2022, is a historical novel that follows the epic and peculiar life of a frontier newspaper typesetter. As part of my research I made extensive use of newspaper archives and, in this series, I’ll share some of my often surprising findings. Here are history, commentaries and contemporary newspaper articles as they relate to my latest novel. This time, a look at the perilous lives of newspapermen.

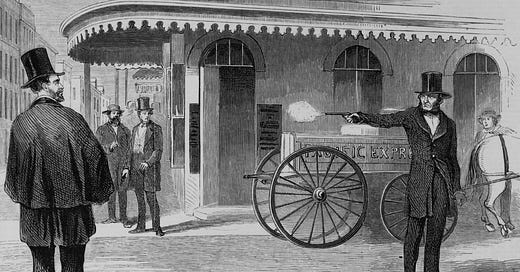

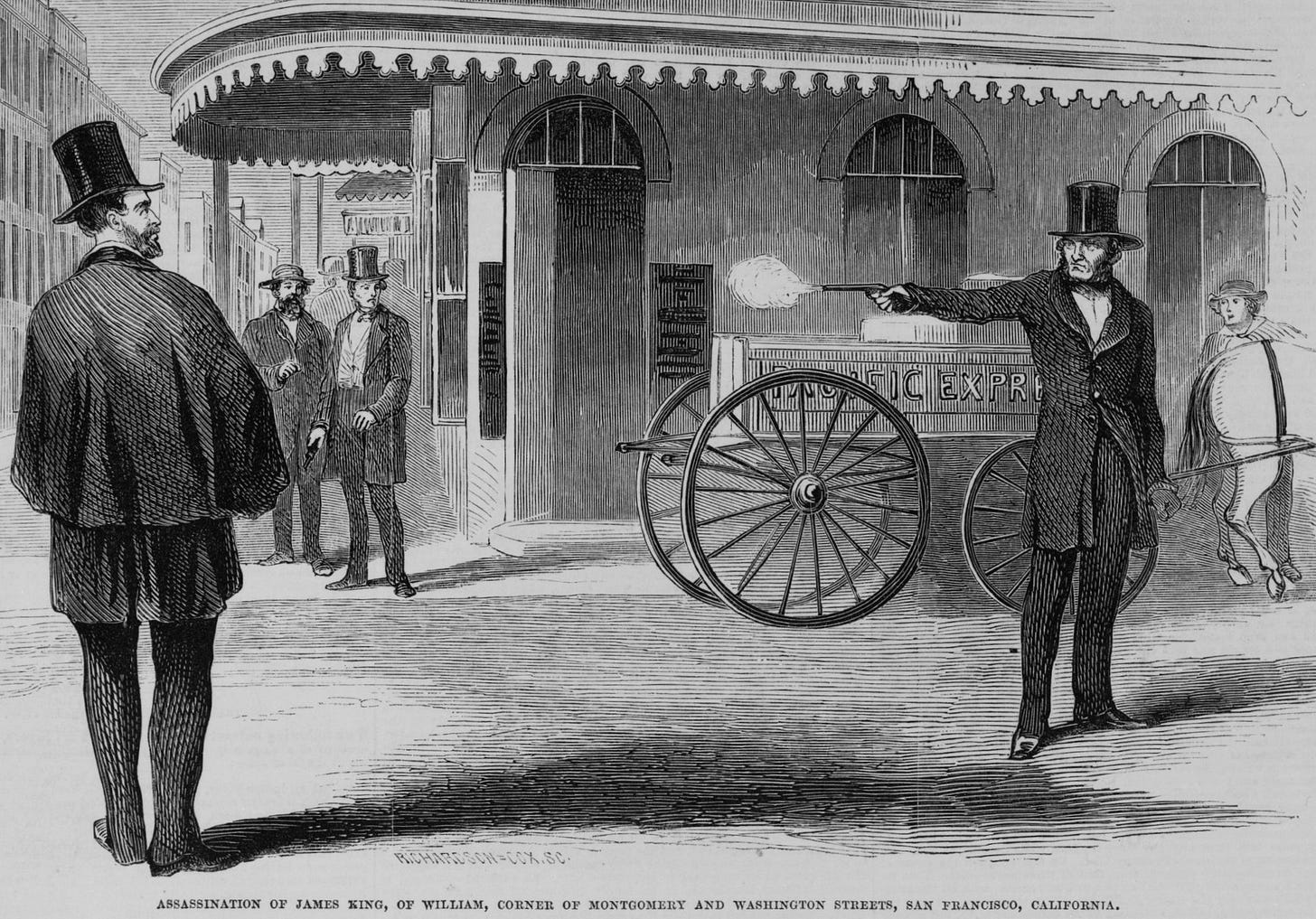

The above image depicts the 1856 murder of James King of William in San Francisco. He had been an outspoken newspaper editor and his death was the result of a feud with another paper’s editor. The below story focuses on another feud, this one involving Edward Gilbert, editor at the Daily Alta California. In an early version of the novel, a friend of young Quintus (you’ll find that early version’s chapter below the newspaper article, printed here exclusively).

The article of the Sacramento Daily Union offers quite a glimpse into the mechanics of dueling, and the tremendous outpouring of grief. It has been said that citizens of boomtowns tended to embrace any and every occasion to celebrate – whether in joy or in grief.

At a later point in the novel, when Quintus works for Virginia City’s famed Territorial Enterprise, there’s mention of another one such duel. The editors of two rivalling papers, Joe Goodman and Tom Fitch, dueled, with the result of Fitch getting shot through the knee. Incidentally, that duel only came about at second try.

The first time it was stopped by the law, and Mark Twain (who later only narrowly avoid his own duels by skipping town), then a reporter at the Enterprise, dutifully reported on it in the paper. Such duels, whenever possible, were not deadly – and they ended neither rivalries nor friendships. The newspapering community was close-knit. Tramp printers, editors and reporters often moved from place to place and formed relationships for life – sooner or later, they all met up again.

August 3, 1852

Sacramento Daily Union, Sacramento

Fatal Duel – Death of the Hon. E. Gilbert.

It becomes our painful duty to announce the deplorable termination of a duel, by which the community has lost a gentlemanly and honorable member, and the editorial profession an able, honest and worthy brother.

On Monday morning, at sunrise, a hostile meeting took place at Oak Grove, between Hon. Edward Gilbert, senior editor of the Alta California, and Gen. J. W. Denver, State Senator, from Trinity county. The immediate cause of this lamentable affair was a card published by Gen. Denver, reflecting upon the personal character of Mr. Gilbert. Of the merits of the controversy this is not the time or place to speak. Mr. Gilbert challenged the adverse party. The weapons selected were Wesson's rifles, and distance forty paces.

After the first interchange of shots, neither of which took effect, the weapons were reloaded and the word given, when Mr. Gilbert fell almost instantly, having received the shot of Gen. Denver in the left side just above the hip bone. The ball pierced the abdomen and passed entirely through his body, coming out on the right side almost directly opposite the point where it entered. Mr. G. survived but four or five minutes after the occurrence, and without a word or scarcely a groan his spirit passed from earth. His body was immediately conveyed to the Oak Grove House, where the sad duty of preparing it for its last resting place was performed.

The most intense sensation was produced throughout the city on the receipt of the mournful intelligence, and all seemed to unite in the sincere sorrow evinced at the unfortunate issue of the encounter, and in the deep and heartfelt sympathy expressed for the surviving relatives of the deceased.

At half past three o'clock in the afternoon, a number of the personal and professional friends of the deceased repaired to Oak Grove, and in the evening escorted the remains to the city. — After the corpse was placed in the coffin, Rev. O. C. Wheeler arose and addressed the company present in strains of touching and melting pathos, and concluded with the most appropriate and eloquent prayer that we ever heard. He made allusion to his long and intimate friendship with the deceased, passed a beautiful encomium upon his moral worth, and inveighed, though gently yet most powerfully against the cruel and bloody code by which he had been cut down in the flower of his youthful manhood and usefulness. Never have we witnessed a ceremony so solemn, so deeply impressive as that brief address and heartfelt prayer in the presence of the dead. There were stout hearts and eyes unused to weeping there, but many a manly tear was shed over the untimely bier of the departed.

The remains were conveyed to the residence of Alderman Nevett, where they will remain till to-morrow, when they will be taken to San Francisco for interment. In the name of the friends of Mr. Gilbert, we thank the proprietor of the Oak Grove House for his kind and generous conduct on this lamentable occasion. We are also under obligations to various gentlemen for delicate and well-timed attentions.

Mr. Gilbert was formerly a resident of Albany, New York, emigrated to this State in 1846, was a member of the Constitutional Convention, and afterwards elected to the Lower House of Congress. He has been for the last four years the senior Editor of the Alta California, and was about 33 years of age at the time of his decease.

We shall take occasion tomorrow to say something on the subject of duelling in general and in detail.

Here the aforementioned chapter that didn’t make it into the final novel. It contains a moment between Edward Gilbert and the young Quintus Hopper, and also details Robert Semple’s thoughts about the duel and subsequent funeral march. Semple was not just the owner of the Daily Alta California (where Gilbert was employed as editor and Quintus as a printer’s devil), he was also, like Thomas O. Larkin, a father figure for Quintus.

THANK YOU FOR THE ORANGE

When Semple had first brought the boy named Quintus to the premises of the Alta, Edward Gilbert had been less than pleased and had made his displeasure known. The paper was no playground and it would not do that type and press workers wasted time minding a child.

“Give the boy a chance,” Robert Semple had simply said and added, with an unfamiliar warmth that was nothing short of perplexing to Gilbert, “he just may surprise you.”

While he maintained his opposition, he acceded to the request because Semple was, after all, the paper’s owner. That was what he told himself. The truth was less factual and thus entirely unacceptable to the mind of Edward Gilbert. The truth was that he had seen something in the boy, the moment he had met him. There had been a calm in those eyes, a calm beyond age, beyond time, a calm that was both striking and utterly disconcerting.

Gilbert and Semple had known each other since the time before the gold rush. It seemed a lifetime ago. Semple was thirteen years his senior and Gilbert often saw, in the actions of the stoic giant, the man he hoped to be someday. Both had worked in the printing business from an early age, both had come to California and fought in the Mexican-American War. What Gilbert consistently admired in Robert Semple, was the man’s courage – it was never proclaimed, it was simply and quietly lived.

Semple had founded the state’s first newspaper. Semple had brought the first steam press to California. He had a way of leading that often left Gilbert with a sense of awe, and a sense of despair. He was doubtful that he had it in him to live up to the example of the towering Semple. But Gilbert strove toward that goal. He had become the youngest delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1849 – and it was his name on the paper, and his business arrangement with Kemble and Hubbard, that ran the Alta California. And yet, he knew that the paper’s true strength lay with that uncanny stillness that was Robert Semple. The man was heart, the man was courage, the man was foundation. It was ludicrous thinking. Ludicrous, Gilbert knew. His worth no less than that of Semple, no less than that of any man. Why then did he lie awake at night, wondering who he was?

Quintus had been with them for more than a year by that time. The boy was punctual, diligent and orderly, there was nothing he needed to be reminded of, ever. Gilbert found himself going to the back more often than he used to. He’d watch the boy, back at the type cases. Quintus would separate type, sort type, clean type and do it over again. The place had never been as clean. With that calm of his, even during the fire a year ago, the boy never failed to do the job. Yes, Gilbert reflected, Semple had been right – the boy had surprised him, and kept doing so.

He had seen the boy arrive early, had taken two oranges from the drawer of his desk and joined Quintus in the back. Now they were sitting on a crate of fresh paper, peeling the oranges and savoring them, one carefully separated slice at the time. Gilbert watched the boy from the corner of his eye. Quintus seemed far away as he ate slice after slice, his eyes fixed on nothing.

“What’s on your mind, Quintus?”

“… Savages,” the boy said, his eyes still far away.

“Indians?”

“Yes, Sir. Everybody calls them savages. In our paper, too.”

“You don’t think they’re savages?”

“I looked it up, the word. It stands for barbaric and cruel. They are not cruel, Mr. Gilbert. We are cruel.”

Gilbert fixed his eyes on the boy, eleven years of age and, somehow, old. Wisdom seemed to shimmer in those gray eyes, like an undiscovered country beyond the horizon. Indians. Why was the boy thinking about Indians? He was right, of course. As right as Robert Semple who, in the past year, had taken an ever-greater interest in the conquering horde’s false narrative. White man had manifest destiny on his side. This was God’s country, this was his country … and no one would stand in the way. Just like Semple, Gilbert was increasingly questioning the stories told by miners, by settlers, by the military. Just like Semple, he saw the lies, blatant, self-righteous … cruel. And just like Semple, he felt powerless at times, weary against the onslaught of deceit. He quietly vowed to himself to do more, to stand up, always, to confront, to never give another inch when truth was at stake. And in that moment, he knew who he was. Edward Gilbert was truth.

“Can you write?” Gilbert asked the boy.

“Yes,” Quintus replied.

“What I want to know is, do you have a talent for it? Would you write something for me?”

“I don’t think so, Sir,” Quintus said, wiping his mouth and carefully positioning himself so that none of the fruit’s juice would drip onto the crate.

“Why not? Maybe there’s a reporter in you.”

“I like it back here.”

“With the press?”

“With the type.”

“A typesetter, then.”

“Yes.”

“A proud profession,” Gilbert said, nodding more to himself than to the boy. He remembered himself, a boy, an orphan, placed into a printing office. He had never cared about the work, about the people, about type, as did the boy next to him. Quintus had taken a single bit of type from his pocket and just looked at it. The letter Q, the one Semple had given the boy when first they had met. What’s with the Q? Questions.

“I have to sweep the floor now, Sir,” Quintus said. Surprised, Gilbert noticed that he had lost time and that the boy was still sitting there, with the last slice of his orange long gone.

“Of course, you go right ahead.” Gilbert rose, self-consciously brushing jacket and trousers. He noticed that he had dropped a bit of orange peel and stooped to pick it up. The boy was already sweeping the floor boards with a broom twice his size. Gilbert smiled and walked away.

“Sir?”

Gilbert turned and saw the boy looking at him, broom in hand.

“Yes?”

“Thank you for the orange.” Quintus gave a quick smile and Gilbert returned it. Then the floor had the boy’s full attention once more.

As Robert Semple followed behind the hearse, he felt more hopeful than he had in a long time. Thomas Larkin was one of the pallbearers and he had been set to lead on the opposite side. Instead he had chosen to follow the hearse in a carriage where he sat alone. The time was his, and the time was Gilbert’s. The service over, the procession now made its way through the streets of San Francisco toward the cemetery. Semple noticed a smile on his face when he mused that, at this pace, they might all be dead by the time they got there. At the head of the procession music played as if the weight of the world hung on the instruments. Then followed the California Guard and then, before the hearse, Reverend Hunt. Left and right of the hearse six pallbearers each, and then there was the tail of the procession, begun by Semple himself. Behind him were three more carriages with Gilbert’s colleagues from the Alta. Then came the Society of California Pioneers, the members of the San Francisco and Sacramento press, associates of Gilbert, friends of Gilbert – and finally the citizenry. A few hundred of them were on horseback … and thousands more followed on foot.

The last time Semple had seen San Francisco this united was during the time of the Vigilance Committee in 1851 – and that unity had come with beatings, whippings and hangings. It had been a time of blood that eventually led to the collapse of the Sydney Duck’s power. Then, they had united to cure the city’s ills by force. Now, they were united in peace, united in the death of one good man. Yes, there was hope for San Francisco. How honest you have been, Edward, how stubborn, and how stupid. Semple, his chin against his chest, slowly shook his head.

Edward Gilbert had been right, of course. Too often had inexperienced settlers lost their strength, provisions and lives in the Sierras as they attempted to enter the land of fortunes. As senior editor of the Daily Alta California, Gilbert had made it his mission to demand action by the government – and he had succeeded. The legislature in Sacramento had appropriated $25’000 to provide relief for overland emigrants and, on June 25, 1852, the wagon train was ready to leave the state capital: eight wagons, packed with provisions, each drawn by four horses, and with spare horses and mules for the long trek to the Carson Valley. Alas, Governor Bigler decided that the good deed should not go unseen by his voters. Placards were mounted on each side of every wagon, bearing in enormous capitals the words, “The California Relief Train.” The governor then rode his horse, the wagons duly following him, through the principal streets of the city. It was nothing but a political show and Edward Gilbert called him out for it … and would soon give his life for sticking to facts and principles.

A few weeks later, members of the California Relief Train came to the governor’s defense with an article in the Democratic State Journal, claiming that the article in the Alta had perfected the facts. A mere two days later Gilbert shot back at them with his next editorial on the matter. He pointed out that, hard as the defenders of the governor might try, “you cannot make a whistle out of a pig’s tail.” Gilbert once more stated his case, for the relief and against the governor’s political stunt, saying that the high and dignified position of Governor of the State of California had been lost sight of by a huckstering politician who was dragging down his office to subserve his personal ends. The facts remained and Gilbert was offering two conclusions to his article: one, that he would continue to expose politicians devoid of principles, and two, that “if any of the gentlemen attached to the train, or any other friend of the governor, desire to make any issue upon the matter, they know where to find us.”

The reply in the Democratic State Journal followed on July 29. Gilbert was called as one of envious and malicious heart. The article ended by stating that, if the editor of the Alta thought himself aggrieved by anything he may have said or done, it was for Gilbert to find him – “and when so found, he may rest assured that he can have any issue upon the matter he may desire.” The article was signed J. W. DENVER.

Just one day later Gilbert’s next missive appeared in the Alta, restating the story and ending by putting his name to it all. “As I am the author of both the articles published in the Alta California,” Gilbert wrote, “which have been alluded to by you as above quoted, I find it my duty to demand from you a withdrawal of the offensive and unjust charges and insinuations which you have made.”

Denver didn’t hesitate: “In reply to yours of the 30th ult., I have only to say that not one word of the cards you allude to can be withdrawn by me until the articles calling them forth are withdrawn by you.”

Semple had followed the back and forth and had finally taken Gilbert aside, ordering him to calm down. None of it was worth a physical altercation, it most certainly didn’t warrant a duel. He should have seen it. Gilbert had said nothing, had given a curt nod and left Semple’s office. He proceeded to demand satisfaction of Denver, General Denver, a man accustomed to the proficient handling of weapons. Rifles at forty paces were chosen … and Edward Gilbert turned to kill or be killed. He shot, and he missed. Denver, calmly, turned his rifle away from Gilbert and fired his round into the air. That could have been the end of it, an honorable way for both to end their confrontation.

Semple sighed. He had been told the story by Gilbert’s second. Both seconds had asked if the duelists were satisfied and Denver had graciously said yes. There was dishonor in ignoring such a challenge – but there certainly was no honor to be gained from actually killing that newspaperman. To everyone’s surprise, Gilbert had refused and demanded a second shot. Rifles reloaded, forty steps taken, the men once more turned and fired – this time Denver didn’t hesitate. He had seen Gilbert’s eyes, a wild determination, uncertain lightning, eager to strike. Gilbert was quick on the second turn, Denver was quicker.

“Truth matters.”

Apparently, those had been Gilbert’s only words before passing away, moments after being shot. Truth matters … it did, indeed, Semple thought. But Semple had no doubt that he’d take the lie for the truth, if it would return the life of Edward Gilbert. You stupid, stupid man. The music had stopped for an instant, the march halted. He saw people lining the streets, crowding, solemn. San Francisco lay there muted, as if the city itself was mourning for one of its own.

It was then that Semple noticed Quintus. The boy was standing by the side of the street, Margit next to him, Nelson behind them like a fearsome guardian. They all wore black ribbons on their arms. The boy and the newspaper owner looked at each other, each giving a light nod. The boy seemed as calm as ever. Semple knew that Quintus and Gilbert had been on friendly terms. Eating oranges in the back – Semple had joined them on a few occasions. Never more.

Then the band launched into another sorrowful march and the procession continued. In a moment, the boy was gone from sight. Not for the last time, Semple wondered whether bringing the boy into the world of newspapering had been the good idea he had thought it to be at the time. Newspapering wasn’t supposed to be a deadly business, but that particular bit of news had not yet arrived in the west.

The Bella Union, the El Dorado, the banks and every other business on Montgomery, all were closed and Semple marveled at the silent multitudes as they made their way to Yerba Buena Cemetery. Semple remembered the reverend’s words: “Fellow survivors, you and I must also die. Therefore, while we admire the virtues of those who have gone before us, let us imitate them. And while we look with charity upon their faults, let us avoid them. And while we feel at this moment the solemnity of death, let us from this moment feel also the solemnity of life.”

Most of those people lining the streets had never met Edward Gilbert. They were not there for the man, they were there for the ideals he had stood for. The ideal of steadfastness, the ideal of honesty, of truth … Truth matters.