The magnificent Maltese Falcon - from novel to film(s)

Just recently I read Dashiell Hammett's 'The Maltese Falcon' for the first time. It felt a great deal like watching the iconic John Houston/Humphrey Bogart film ... and so I took a closer look.

I mean, who hasn’t heard of The Maltese Falcon, right? And for most of us it’ll mean instant memories of Humphrey Bogart in the role of Sam Spade, the ultimate private eye. You’ll also remember Mary Astor, Sydney Greenstreet, Peter Lorre, the fantastic plot, and the dialogue, man, that dialogue it’s, you know, the stuff that dreams are made of.

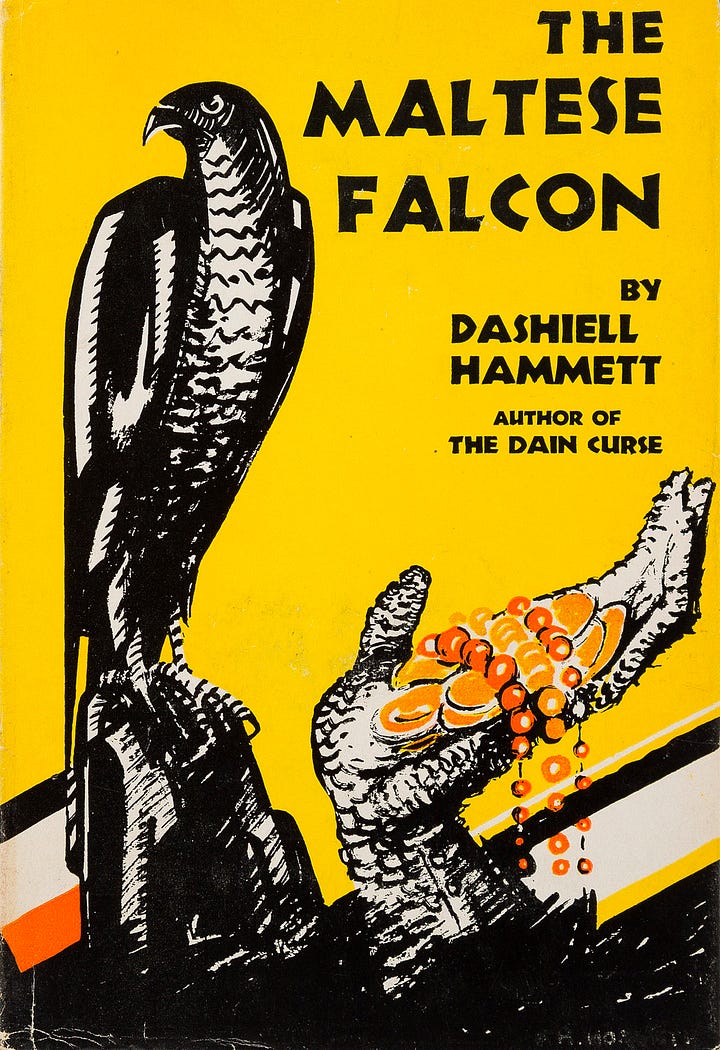

Well, there’s that film and, frankly, if that’s all you’ll ever know about The Maltese Falcon, you’re wonderfully served. But did you know, for example, that several Maltese Falcon films were made? But more on that later - first about the novel. Dashiell Hammett wrote it in serialized form in the late 1920s, it was then published as a novel in 1930.

If you’re a screenwriter like me then this novel will feel to you like a screenplay. Screenplays are extroverted. In them you read what happens on screen, what is seen, what is said, what is heard. Novels, most often, are introverted. They’ll come with a lot of character musings, we get to be in their heads, read about their thoughts, get to know them beyond their external actions.

Not so in script, there’s not a single line in a screenplay about what’s happening inside a character’s head - there is only what they say, what they do, how they act and react. In Hammett’s novel then, he does just that - there’s nothing about what characters feel or think. Made me feel right at home as a screenwriter and, frankly, John Huston (who directed and also wrote the screenplay) must have felt the same way.

I’ve written a few adaptations (more on that here) and can tell you from experience that, most often, they’re far from easy. In the case of the Maltese Falcon, however - man, John Huston was gifted with a rare novel that had it all laid out and ready for him in entirely cinematic ways.

This film, by the way, was Huston’s directorial debut - and his very fruitful collaborations with Humphrey Bogart (such as The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, The African Queen, Key Largo) really only came about by chance, because the role of Sam Spade was offered to George Raft first.

Aside from the novel being very script-like, it was also startling to me just how faithfully the iconic film follows the novel. For much of the novel I could just see Bogie and Mary Astor and the rest of the amazing cast - the lines were there, word for word, the actions, the big things, the little things - seemingly all there. Obviously, a number of things had to be cut to pack it all into the film, but, again, faithful as can be.

However, that iconic line I mentioned in the opening paragraph? “The Stuff that dreams are made of” - that awesomely epic line - is not in the novel (legend has it that Bogie himself suggested that line). I’m sure Hammett didn’t mind that particular addition!

Oh, since we’re on the topic of Humphrey Bogart - he was nothing like the Sam Spade Hammett had created in his novel. The original Sam Spade was a blond hulking pack of muscles with - get this - eyes that often appear yellow! The novel’s Spade is also a lot meaner, spiteful, occasionally petty, downright cruel. Bogart plays all of that to some degree, but he gave us a Sam Spade who’s tough as nails while, underneath, we can always feel that there’s a cool and mature soul with, ultimately, the heart in the right place.

Well then, should you ever feel like going down the Maltese Falcon rabbit hole, then know that watching the Huston/Bogart film is a great starting point. Now pick up the novel and know that it’ll be like watching the movie, but it still offers a few surprises - such as the “Flitcraft Parable” … at some point in the novel this feels like the author’s giving us a break, a time-out, an intermezzo from the twisted plot.

Sam Spade hangs out with Bridget O’Shaughnessy and tells her the story of a man name Flitcraft, who, after almost being killed by a falling beam, just leaves his family behind and vanished. I’ll let you read that short story (3 pages in the novel) here. It certainly is an unusual element in The Maltese Falcon. Clearly, the story means something to Sam Spade, he likes that “He adjusted himself to beams falling, and then no more of them fell, and he adjusted himself to them not falling.”

If you’d like to know a bit more about this oddly central bit in Hammett’s novel, here’s a thought piece about it in The Guardian.

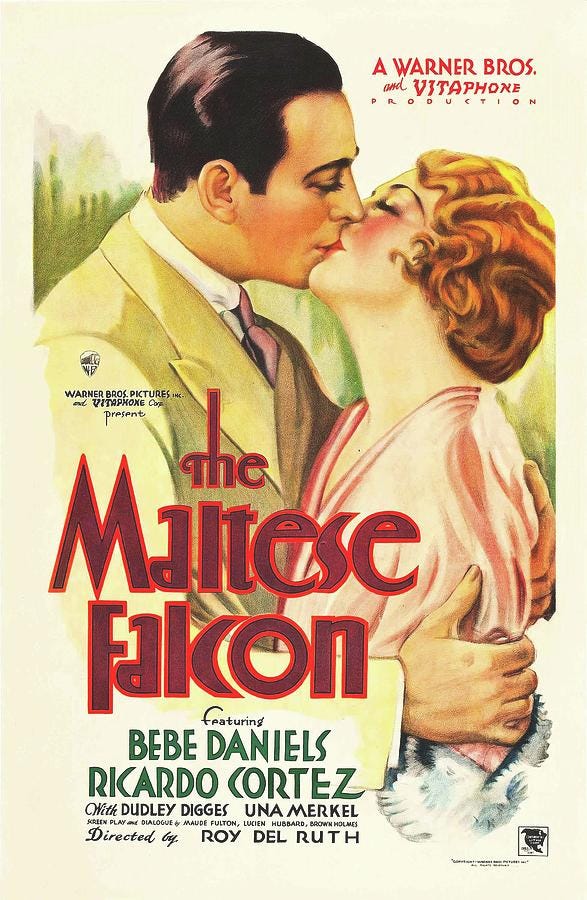

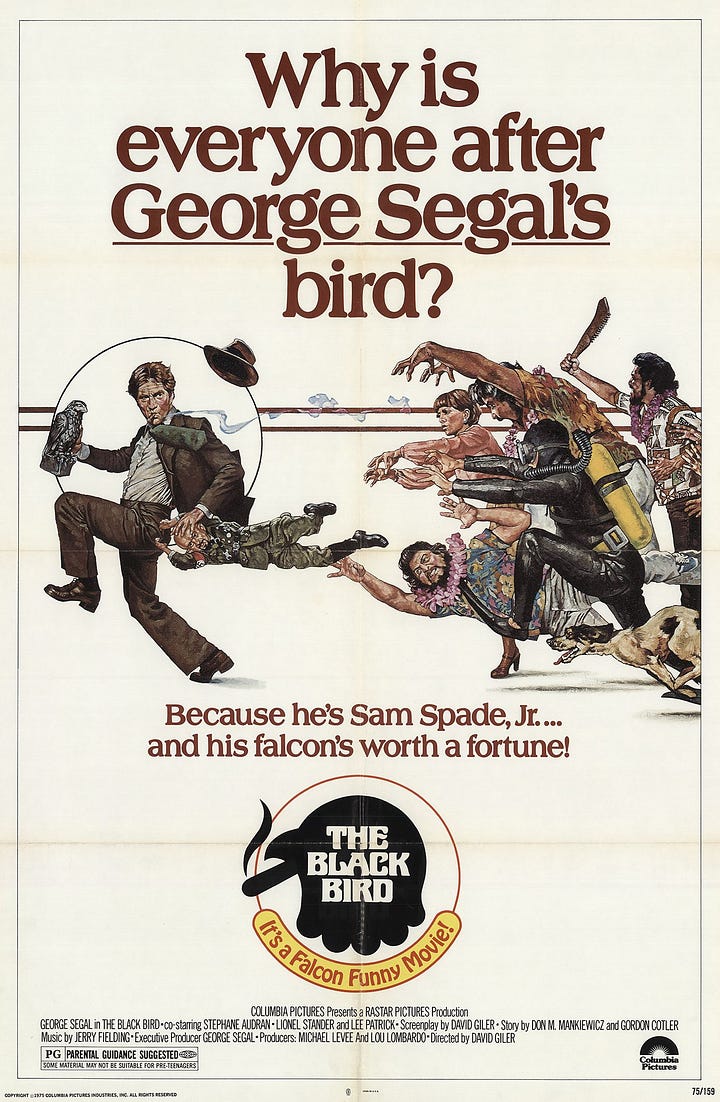

And when you’re done reading the novel, then why not check out the other Maltese Falcon movie adaptations? The first was made in 1931 (10 years before the Bogie version) and pretty much vanished for many years because it censors denied approval as the film was considered to contain lewd elements. The second film followed in 1936 and was called Satan Met a Lady - it starred Bette Davis and was more of a comedic take on the novel. Another ‘funny’ adaptation came about in the seventies, a film called The Black Bird, starring George Segal as Sam Spade. I have to say, I haven’t seen these three films, but now that I’m writing about them, I really want to!

… well, I couldn’t wait and found the 1931 Maltese Falcon online - watch the full movie right here.

Cheers!

D

The Maltese Falcon is my favourite Bogart movie but I've never got round to reading the book. I must do that. Oh, and on the next rainy Sunday afternoon, I'm going to watch the movie again, too. Thanks for the reminder.