The fires of San Francisco (includes exclusive chapter)

Every boomtown, put together in days and weeks with nothing but canvas and timber, had its share of fires - but none more so than San Francisco.

Quintus Hopper of Nevada, published in January 2022, is a historical novel that follows the epic and peculiar life of a frontier newspaper typesetter. As part of my research I made extensive use of newspaper archives and, in this series, I’ll share some of my often surprising findings. Here are history, commentaries and contemporary newspaper articles as they relate to my latest novel. This time, a look at the early San Francisco fires.

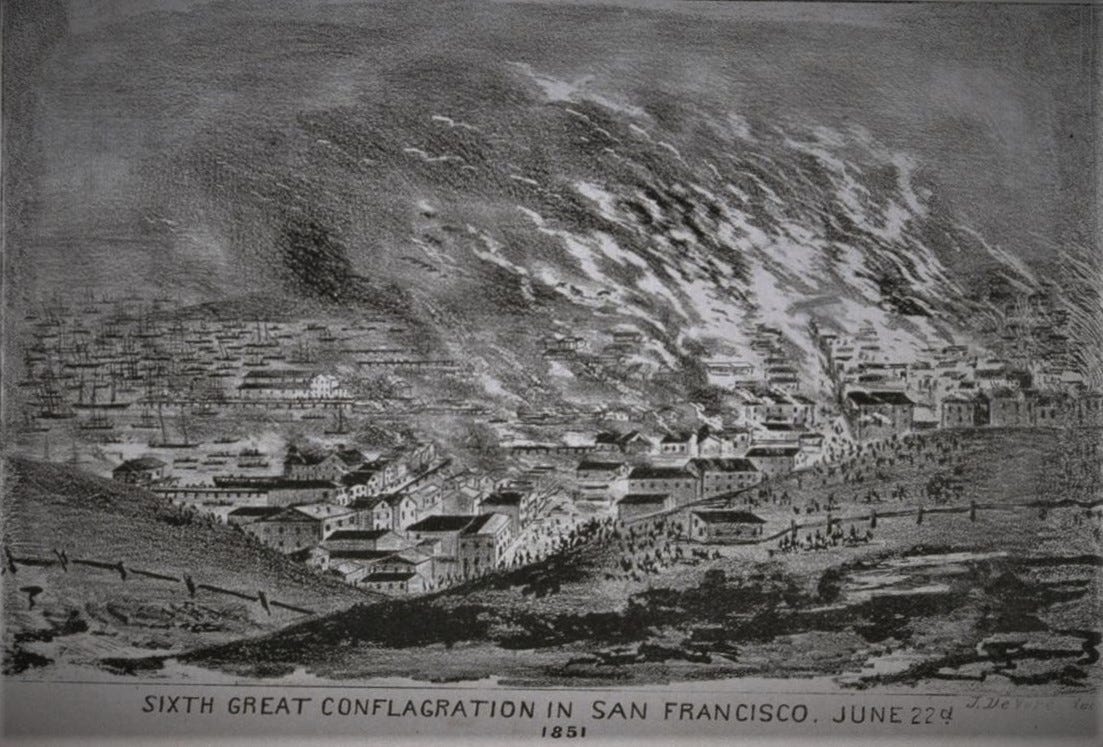

The boy Quintus Hopper becomes a printer’s devil (an apprentice) for booming San Francisco’s big paper, the Daily Alta California. Every boomtown, put together in days and weeks with nothing but canvas and timber, had its share of fires. But San Francisco stood out from every other place as it had grown at an incredible pace, and in that time brought together thousands upon thousands of people and tremendous wealth. In the early years, nothing was built for safety. In fact, Thomas O. Larkin was the first to build a brick house in San Francisco (in the novel it is the place of home for young Quintus). And so the city experienced a series of fires, more than a few due to arson (the infamous Sydney Ducks the likely culprits). The fires are simply mentioned in the novel – but an early version of the manuscript contained a whole chapter about the great fire of June 22, 1851 (you'll find that chapter below the newspaper article, published here exclusively). The fire devastated San Francisco, and also destroyed the offices of the Daily Alta California, the paper in whose employment Quintus works as a printer’s devil. Here the Alta itself reports on the incendiary affair the day after the disaster.

June 23, 1851

Daily Alta California, San Francisco

Our Office. – By the disastrous fire which occurred yesterday our pecuniary loss has been about sixty thousand dollars – our prospective losses we cannot state. We have saved however enough to continue the publication of our paper, which will be issued hereafter regularly as before. Our office for the present will be in the California Exchange, in the office of Berford & Co’s Express, where all advertisements and orders will be attended to as usual.

Another Terrible Conflagration.

Again a large portion of our city is in ruins, and as is believed by many and with good reasons, by the hand of an incendiary. Nearly all the northern portion is nothing but smoldering embers. Eight squares at least are in ashes, and nothing within the boundaries of this immense area can now be seen except a few ghost-like chimneys, remaining like memory when the substance has passed away forever.

At about half past ten o’clock yesterday while some of the bells in the churches were tolling, calling the devotional to worship, smoke was seen issuing from the second story of a house on the corner of Pacific and Powell streets. The fire bells were immediately rung, and the frightful cry of “fire” was raised and echoed through the streets, which were full of people on their way to church. An immense crowd was very soon on the spot and every imaginable effort made to check the fire in its incipiency. But like Hercules it rose superior to all opposition. It was at the windward side of the city and had commenced just at the time when the strong sea breezes usually set in. Soon the breeze became a gale.

Very little water was to be had in the vicinity. It was in a part of the city where none of our previous conflagrations had extended, half a mile above any of the public reservoirs, most of which were nearly empty, and in the midst of the most inflammable portion of the city, all wooden buildings, small, one or two stories, built of very light timber, which caught and burned like shavings. Attempts were made at once to tear down the small buildings near, and some were demolished; but the greedy flames were too rapid and the heat in a very short time became so intense that every person was absolutely driven from the vicinity.

Some of the fire engines were soon on the ground, but they were entirely useless for want of a supply of water. The fire at once crossed over Pacific Street to the South, and down toward the harbor, eastwardly. To the North it swept on to Broadway, leaving no building in its path. To the East it crossed Stockton, Dupont, Kearny and Montgomery, in one place extending as far as Sansome. Its course along Washington, Jackson and Pacific streets, toward the Bay, was over a portion of the burnt district of May 4th. The buildings were in many instances not finished, with shavings and inflammable substances in abundance.

After the fire reached Washington street, the California Restaurant, which adjoined the Alta California office, was blown up, but it did not stop the flames. The Jackson House and Lafayette Restaurant and buildings in the rear, were all on fire at once, and the flames were at the same time enfolding the wooden building formerly called the St. Charles, which stood between the Alta office and the fire proof Bella Union. Thus surrounded and enveloped in flames, all our efforts to beat back the destroyer were vain. With a plentiful supply of water and a fire engine, in addition to the two force pumps of our own, we were perfectly powerless. Yet a dozen men contended long and manfully, risking their lives and doing all that men could do, but in vain. Then and not till then they left, when they could no longer breathe within the building, and rushed through cinders, sheeted flame and dense smoke to the Plaza. Here most melancholy sights met the view. A large portion of the goods removed there for safety were on fire and were totally consumed. Among them was much of our own stock of stationery and material. But more horrible than all, two or three corpses, one of a man who was moved on account of sickness, in his bed, to the Square, and there died while the fire was raging.

Another was the trunk of a man burned to death and partly consumed. The new Parker House, nearly finished outside, containing the new Jenny Lind Theatre, which had been built since the fire of May 4th when the fourth Parker House was burned, went with the rest. This was the fifth burn down since Dec. 24th, 1849. Our own office is merely ruins, only a portion of the walls remaining. Fortunately the Amphitheatre or Circus on the west side of the square had been torn down a few days before, which was the means partially of saving the old zinc custom house building on Clay street, and a few adjoining small wooden houses, and preventing the fire crossing Clay street above the plaza. The old “adobe” on the plaza, in which was the office of Burgoyne & Co., and several, shared the fate of others – it was completely burned. Thus about the last relic of the feudal age of San Francisco has been blotted out. So our poor city is again in sackcloth and ashes. Our community are blank. For although but few heavy stocks of goods or fine buildings have been consumed, yet the blow is felt very severely, for most of the buildings were occupied as dwellings and lodgings. It is too soon to speculate particularly about the effects, except as to general results. Thousands of our people are homeless. We are sick with what we have seen and felt, and need not say more.

Here’s an exclusive chapter from an early version of Quintus Hopper of Nevada. It didn’t make the final cut - but it absolutely is part of young Quintus’ life.

THE FIRES OF SAN FRANCISCO

He was ten, he was a printer’s devil, and he was no stranger to the fires of San Francisco. Quintus had experienced his first San Francisco blaze on September 17, 1850, just a week after starting at the Daily Alta California. It had eaten through new buildings just a block away of Larkin’s house. Quintus had heard the cries and the bells hours before sunrise and had helped Margit and Nelson as best he could, dousing the walls and roof of the house with water. The Larkin house was spared that night and every night. And sometimes it was luck, and often it was Margit and Nelson who defended the house at all peril and cost as if it were their child. They had the burns to prove it – and while they didn’t require Thomas Larkin’s gratitude, he never failed to give it.

The fires continued. Sometimes they’d be caught in time, with no more than a few buildings stolen. And sometimes they would be remembered in history as the great fires of San Francisco. What would never be known was that the boy had helped stop many more fires that would have been. Quintus was an avid listener and, as he understood that which anyone spoke in any language, he would hear whispers of plans and murmurs of arson in the streets. The first time that happened, he had confided in Margit – and as she shared everything with Nelson McMahan, in their days and in their nights, she also shared what Quintus had told her.

“You’re telling me the boy speaks all languages? All of them?” Nelson asked.

“That’s what I’m telling you, Nelson,” Margit replied. “But that is not what’s important right now. Have you heard what I told you?”

“No one speaks every language, Margit. That just not possible.”

They had shared the bed and she was in his arms, still. Exasperated, she extricated herself and sat up, glowering down at him. He smiled and tried to pull her close once more. When she swatted his hands and the glowering continued, he sighed and sat up as well. Leaning against the headboard of the bed, he nodded.

“So, the boy hears two Germans talk about setting a house on fire. He hears that the Ducks paid them to do the job. He hears about the time and the place … What am I supposed to do about it?”

“You’re supposed to stop it, Nelson.”

“Now listen, Margit,” Nelson said, rubbing his eyes, “Let’s assume the boy really does understand all languages and let’s assume he’s really heard what he told you about.”

“Yes, let’s assume that,” Margit said, her face set in stone.

“Then let’s assume I go out tonight and stop those Germans from laying that fire, all right? I know the Ducks only too well. The only thing that will happen is that those two Germans will be found dead. They’ll be found beaten and burned, but not the faces. They’ll make sure that everyone recognizes the faces of the men who didn’t do what they had been paid to do by the Ducks. And the fire? It’ll still happen, Margit. If not tomorrow night, then the next, or the one after that. You can’t stop the fires.”

“… You can stop this one.”

Nelson had fought every day of his life until he had met Margit. He had fought for life at birth, with his mother losing her last breath so that he could fight to have his first. He had fought into the light, into the cold, into life that was nothing but a seemingly endless sequence of violence. He had fought his father, his brothers, his neighbors, his partners. He had fought on land and at sea, he had clashed, wrestled, battered, maimed and killed. Every dead face before his eyes was numbed and pushed aside by the next, and the next, and the next … he had been so tired of fighting when Margit had stepped into his life. He had almost killed her, too. She was a marvel. She had brought him back. No, she had given him life … she had given him everything he had never been and he would love and protect her to his dying day. Nelson looked into her eyes and took her face in his hands. Margit shook herself free, but he smiled, and he nodded, and she allowed it.

“I will stop this one,” he said.

It became a matter of pride for Nelson. That night he stopped the two Germans from setting the house at the corner of Broadway and Kearney on fire. He wore a hood and scared them within an inch of their criminal lives. He told them in no uncertain terms to leave the city and never return. They did, Nelson found out in the coming days. They left and didn’t die at the hands of the Ducks. No fire that night, no dead Germans … and Nelson felt as good as, before then, he had only ever felt in the company of Margit. From then on, whenever Nelson and Quintus had the opportunity, they were out there, listening. In all, the clandestine duo stopped twenty-seven fires from happening. Something that no one would ever know – and that was just fine by them.

The great fire of June 22, 1851, was something Quintus had smelled before the cries and bells. He had quickly alerted the foreman and the bull of the man had not hesitated. By then he had known that earnest boy long enough. He knew that Quintus spoke rarely and that, when he did, it was worth listening to. He also knew that Quintus had an uncanny sense for the fires of San Francisco, it was as if he were, somehow, in tune with the winds of the bay. The foremen instructed his men to start moving everything that could be carried out of the Alta building and into the middle of the square. While some were still questioning the order, the fire bells were heard. Within moments everyone, including the reporters, editors and Robert Semple himself, were racing to save what could be saved. While the men handled the big machines and cabinets, Quintus looked after type. Whatever case was still around, whatever type was on the floor, or awaiting print in forms, he hurriedly collected and carried to the center of Portsmouth Square where, less than ten minutes later, hundreds of men built up piles upon piles of belongings.

The fire had started in a two-story wooden building on Pacific street, near Powell. A carpenter’s shop next door, Morriss & Reynolds, was engulfed soon after – and that’s when the winds, hurricane-like, fanned the flames. The blaze roared high and wild, traveling south and east in a fury, down Broadway, Pacific, Jackson and Washington. Citizens tore down and blew up buildings to halt the spread of the fire, but hurtling winds carried the embers across the razed lots to the next block and roof. With no water in the area, the people of the city stood powerless, watching the fire take house after house, take City Hall and City Hospital. Closer to the shore, building roofs were covered with wet blankets – a continuous effort that halted the spread of the flames in that direction. A wave of fire rolled toward Portsmouth Square and there, like a claw, it attacked from three sides – with the Alta California building at the very center of the attack.

Semple ordered the destruction of the California Restaurant and the Louisiana, adjoining the Alta California building on either side. Quintus saw him swat aside the properties’ angry owners, exclaiming something about compensation – then sticks of dynamite were hurled, just enough to implode the buildings in plumes of smoke. Semple shouted at the men, directing them, pointing this way and that, rallying them, and Quintus thought he heard hope in the man’s voice … it was gone moments later. The flames licked at the Alta from the back – the whole block between Jackson and Washington on fire now – and soon the sparks reached the newspaper building and Quintus saw Robert Semple pause. He watched the house as it was engulfed in the flames, as if to commit the sight to memory. Then he charged back into action and didn’t rest until the great fire of June 22, 1851 was under control. Half of what surrounded Portsmouth Square had been consumed, including the Parker House and its famed Jenny Lind Theatre, the place Thomas Maguire had already rebuilt five times due to previous fires.

Quintus stayed with the typecases of the Alta California through all of it. The fire brigade had done what could be done against the blazing monster and the winds had finally died down. The boy still saw isolated flames – but now it was mostly the smoke, sluggishly wafting through the cindered streets. People were coughing, wiping their eyes, too tired to be angry, too worn to wail … some stared into space, hands, faces and clothes black with soot, others cried in silence. Far from everything that had been piled into the square had survived. Here, too, embers had been carried. And some of those who had left their belongings unattended found only piles of ashes upon returning. The people in the square had, during the fire, moved and moved the piles, as if playing chess. In this incendiary game, Quintus and his fellow newspapermen had been as industrious as they had been fortunate. All of their equipment was safe.

At the onset of the fire, Margit had rushed to the Alta to tell Quintus to stay with the compositors. The fire was far closer to the Larkin house than it was to the newspaper building, he’d be safer there. It was agreed and Margit rushed back to help Nelson who, together with a number of hurriedly hired hands, labored with all his considerable might to protect the house he had promised to take care of. And that, he did. Larkin had not spared expenses and a separate water tank behind the house allowed the men to wet the building three times, until the blaze had torn past them. When the smoke cleared in the end, they saw that every building around them lay in smoldering ruins – but what damage the fire had done to Larkin’s brick house, Nelson would be able to repair as if nothing had ever touched the residence.

Margit stood next to Quintus, with the boy looking more like a printer’s devil than ever before. Everything about him was darkened by soot, grime and mud. She had hugged the boy, not once but five times, hugged him tightly. He had let it happen, had gently patted her on the pack as if to let her know that he was okay. He had smiled at her then, told her that he was fine. Now he just stood there, as did she. Both of them beyond tired, too exhausted to even think of making the effort of sitting down. So they stood.

As always, Quintus listened. It hadn’t been a conscious effort, but ever since arriving in that swirling pool of languages that was San Francisco, he had learned to make sense of the relentless bombardment of everything he heard and understood. That which would have driven most people insane, the boy simply accepted with utter calm. When a dozen languages were spoken all at once, he didn’t mind listening to all of them all at once. There was nothing confusing to it, nothing aggravating, nothing consuming. Quintus just listened … and sometimes chose to listen more closely. As he stood with Margit, men, women and children were in the square with them. A woman, cradling a baby, cooed a Russian lullaby. He still occasionally came across languages he couldn’t name – but after a year in the city he could identify most of what he heard. Two men behind Quintus were murmuring in Gaelic, defeat in their voices, talking about returning to the east coast. To his right, a Mexican family of seven, a stone-faced father, and a mother’s words that carried hope for the benefit of the little ones.

Then there was Robert Semple. Like a tiger, he had circled the piled property of the Alta for the past hours. He had talked to everyone, thanked his men, passed on instructions and organized the future of the paper. Quintus saw him shake hands and heard him inform his people that, within the hour, they could start moving the equipment to the California Exchange. The building on the east side of the square had miraculously been spared and stood there, tall and whole, a sign, a signal, a symbol that there was life beyond the ashes. With the business of the paper’s immediate future taken care of, Semple turned to join a group of men, men of importance, men of wealth. Quintus couldn’t hear what they talked about, but he saw their faces, dark and severe – and once in a while their anger amplified concerns and hurled words like arson, justice and hanging beyond their numbers. Quintus had heard and read about the Committee of Vigilance as the announcement of its formation had been printed in the Alta just ten days before. Quintus remembered every word of that announcement as one of the typesetters had allowed him, for the very first time, to set type. Even with the composing stick large in his small hands, he had set the column expertly, without flaw, without dropping even a single type, and at a speed that startled the weathered compositor at his side. Now, watching Semple and the others bound in heated conversation, Quintus uttered, barely audible, what he had composed.

“Whereas it has become apparent to the citizens of San Francisco that there is no security to life and property, either under the regulations of society as it at present exists, or under the laws as now administered, therefore, the citizens whose names are hereunto attached, do unite themselves into an association, for the maintenance of the peace and good order of society and the preservation of the lives and property of the citizens of San Francisco, and do bind ourselves, each unto the other, to do and perform every lawful act for the maintenance of law and order, and to sustain the laws when faithfully and properly administered. But we are determined that no thief, burglar, incendiary or assassin shall escape punishment either by the quibbles of the law, the insecurity of prisons, the carelessness or corruption of the police, or laxity of those who pretend to administer justice.”

“Did you say something?” Margit asked, when she noticed Quintus staring at the circle of men.

“No,” Quintus said.

“You’ve done good, Quintus,” the foreman said, laying a large hand on the boy’s shoulder. “Now you go home, you hear? I don’t want to see you until three o’clock tomorrow afternoon. It’s been a hell of a day and we all need the rest.”

He gently pushed Quintus to Margit and walked away with a tired smile that faded into exhaustion the moment he knew he was beyond the eyes of the boy.

“Let’s go home,” Margit said.

“Margit,” Quintus said, his eyes on the group of men again.

“Yes?”

“The Committee of Vigilance, they want everybody to be safe, right?”

“Don’t worry about them, let’s go.” When Quintus didn’t budge, she sighed. “Security, order, peace, yes, that sort of thing. A safer place for everyone.”

“… For the Indians, too?”

“What?” Margit asked, perplexed. “What about the Indians?”

“You said a safer place for everyone … the Indians are a part of everyone, right?”

“… Sure, I suppose they are …”

They made their way home, walking along Dupont and Jackson, with the blocks on either side charred and flattened. Ahead of them, like a valiant knight still standing tall on the battle field, stood the Larkin house. Nelson waved when he saw them approach and Margit’s heart surged as it always did when she saw the wild man of Ireland who had been tamed by the horrors of San Francisco and the love of a Hungarian woman. Before falling asleep that night, she told Nelson about the conversation with the boy.

“Why’s he worried about the Indians?” Margit mused.

“I don’t know, Margit,” Nelson replied, already half asleep.

“He’s a strange boy, isn’t he?”

“That he is, Margit. That he is,” Nelson murmured.

They fell asleep at the very same instant, just moments later, and they both met an old Indian woman in their dreams. They sat by a warming fire, somewhere in dark wilderness, surrounded by rocks and stars, listening to stories about wolves and coyotes and first and second people. The woman was full of heart, and full of a warmth that was worlds beyond the warmth of the fire. When they woke the next day, they remembered everything. Margit told Nelson, and Nelson told Margit – and they wondered how they could possibly have had the same dream. The Indian woman had been, without a doubt, the woman in the painting above the mantelpiece. The dream would remain vivid in their minds, the woman, the warmth, the stories … and for years to come that dream was one they hoped to return to, every time they closed their eyes.