Rogue Male: The anarchic aristocrat

Both "The 39 Steps" and "Rogue Male" are about a protagonist hunted in England by nefarious German spies. Both offer excellent stories, and they couldn't be more different.

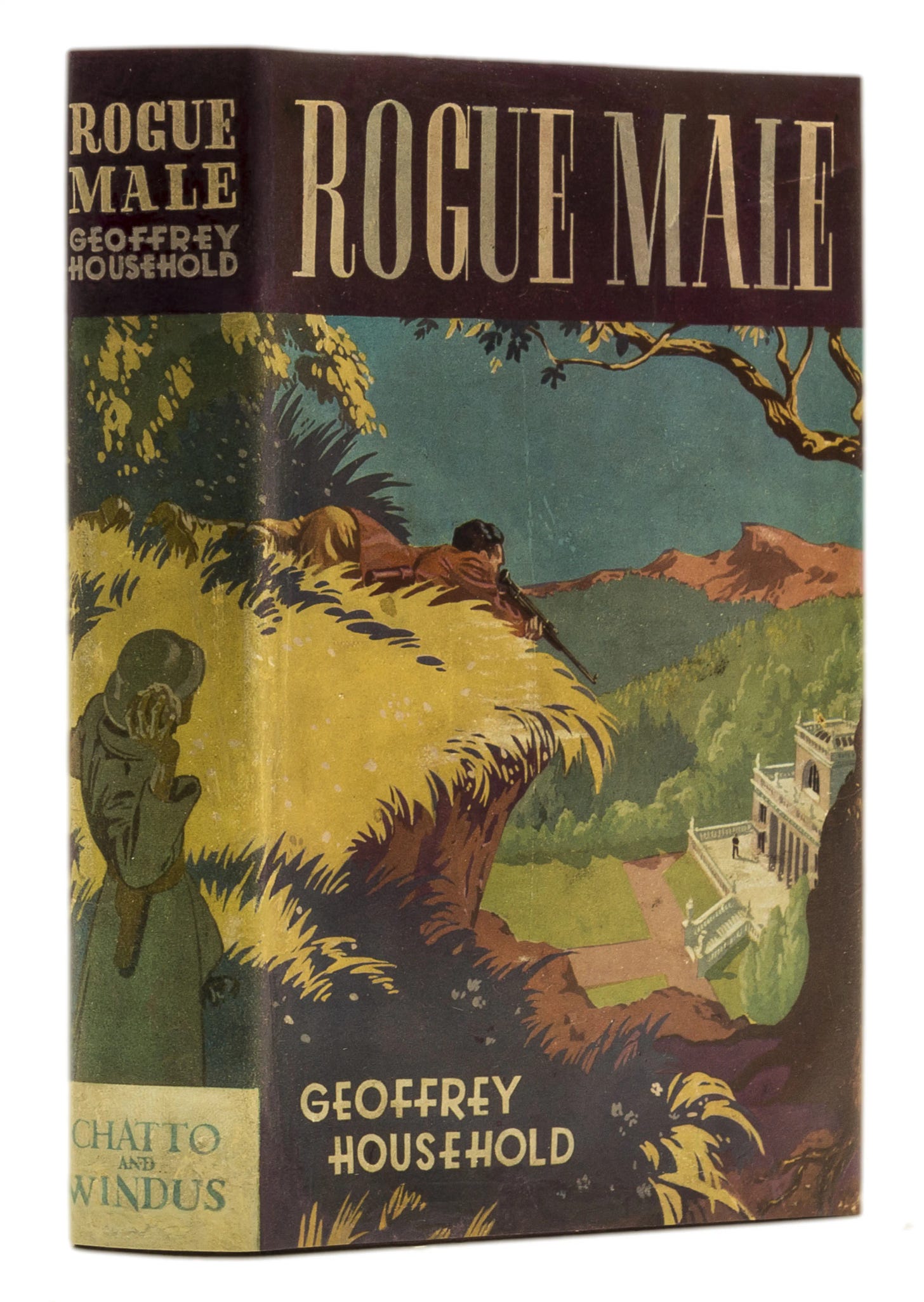

I’ve written about the many, many adaptations of The Thirty-Nine Steps the previous week. It is a fast-paced ripping yarn by John Buchan that gave rise to the “innocent man on the run” genre. But if I’d have to choose between that one and Rogue Male by Geoffrey Household, I wouldn’t hesitate for a second - it’s the latter by a mile. Luckily I don’t have to choose, since both tales are absolute classics.

I first knew about Rogue Male because of the movie adaptation starring Peter O'Toole, but I had never read the novel and had never seen the film. Of Fritz Lang’s Hollywood adaptation, the 1941 Man Hunt, I had not even heard of. We’ll take a closer look at the two adaptations in the second part of this post.

This novel, this novel … what a strange animal

Animal actually is quite a suitable way to describe it. In nature, a rogue male is a solitary male, wild animal. And that very much is what the hunted protagonist more and more becomes. Like I said, I very much love “The Thirty-Nine Steps” - it comes with a classic protagonist who’s thinking, behavior and actions are crystal clear. The protagonist of “Rogue Male”? Not so much!

“The behavior of a rogue may fairly be described as individual, separation from its fellows appearing to increase both cunning and ferocity. These solitary beasts, exasperated by chronic pain or widowerhood, are occasionally found among all the larger carnivores and graminivorcs, and are generally males, though, in the case of hippopotami, the wanton viciousness of old cows is not to be disregarded.” (Geoffrey Household)

Both novels are first-person narratives - but while one makes perfect sense as our on-the-run hero tries to navigate everything and everyone on his way, the other ruminates in ways that are not readily accessible. Clearly, I very much prefer the mystery, the strangeness of the Rogue Male - I’m calling him that because the protagonist never even gives us his name. Sometimes he is incredibly clearheaded, and sometimes he’s an unreliable narrator, uncertain about his own motivations - and does his best to keep his emotions at bay.

“I have never taken sides, never leaped wholeheartedly into one scale or the other; nor do I realize disappointments, provided they are severe, until the occasion is long past. Yet I am ruled by my emotions, though I murder them at birth.”

So it begins

This incredible tale begins with our hero on a hunting stalk. We’ll eventually hear that he’s a famous English aristocrat and big game hunter. Here, he’s chosen to walk for hundreds of kilometers on his own and just with his rifle to … the country residence of one Adolf Hitler. He tracks guards, finds his place and time, takes aim when Hitler stands outside - but is caught before he gets to pull the trigger.

Or, was he even going to? They can’t really get the measure of this strange man. With his British passport, is this man, clearly a gentleman, a spy? Or was he on his own? An avenging angel? Did he come here to assassinate the Great Man (this is what Hitler is called in the novel - neither the name Hitler nor the country Germany are ever mentioned)?

In the notes he eventually sets down, he writes:

“After two or three hours of their questions I could see I had them shaken. They didn’t believe me, though they were beginning to understand that a bored and wealthy Englishman who had hunted all commoner game might well find a perverse pleasure in hunting the biggest game on earth. But even if my explanation were true and the hunt were purely formal, it made no difference. I couldn’t be allowed to live.”

The Germans torture him, pull his fingernails (there are some very brutal elements in this novel), beat him to a bloody pulp and whatever else they can think of. They can’t let this well-known British aristocrat live a) because of what they say he tried to do and b) because of what they have done to him. It would create an international incident.

So what to do? They drag him to a cliff where they let him hang by just his bloody fingers (that way the torn fingernails will be explained). Then they kick him off. The officially story is that the man was on the hunt and lost his footing and fell and died. Except that, when they look for him later, they cannot find his body.

“I had crashed into a patch of marsh; small, but deep. I couldn’t see or feel how much damage had been dealt. It was dark, and I was quite numb. I hauled myself out by the tussocks of grass, a creature of mud, bandaged and hidden in mud.”

Thus begins his grueling trip back to England. He cannot walk, crawls his way forward and improves little by little. With cunning and determination he eventually manages to get back to London - where he realizes that nothing is settled. The Germans didn’t give up looking for him and when he shows up at his solicitor’s, it becomes clear that they’ve been waiting for him. A chase ensues and one of the henchmen lies died - now our hero is also sought by the local police.

The man claims that tracking Hitler was just a game. He wanted the sense of adventure. He wanted to see if he could get close enough. And that he could have, should he have wanted to, kill the Great Man. He claims that, of course, he didn’t plan to actually kill the man.

“Now, I argued, here am I with a rifle, with a permit to carry it, with an excuse for possessing it. Let us see whether, as an academic point, such a stalk and such a bag are possible. I went no further than that. I planned nothing. It has always been my habit to let things take their course.”

Later on we shall discover that there very well may have been a reason. A woman. Killed by the Germans. Yes, he would have killed Hitler. Now he’s on the run in England and he doesn’t do what anyone else likely would have done: like going somewhere far away, leaving the country, assuming another identity, etc. Nope, this hunter does what a hunted animal would do - he “goes to ground”. He literally goes underground.

He manages to build himself a burrow in a hedge where he makes himself quite comfortable, where he decides that he can wait it out for months, where he makes friends with a cat, where he simply stays, and observes - utterly at peace. The problem is that the Germans have the equivalent of the hunter he is, and that spy manages to think like he does and little by little closes in - until he actually discovers the burrow with our hero now caught with no way out.

I won’t tell you any more of this story - you can already see just how curious a tale this is: a very unusual narrator, both of character and of state of mind; choices, decisions and plot elements that you wouldn’t normally come across; and then it gets so intensely close that antagonist and protagonist are separated only by clumps of earth. What happens then, what the German wants, how our hero reacts … it’s all quite unique. Like I said, a very, very strange tale - with an equally strange hero.

The film adaptations

As a screenwriter I’ve been employed to adapt four novels. The process of adapting someone else’s creation to the medium of film is invariably fascinating and when I see adaptations of novels I’ve read, I cannot help but look at them from the point of view of screenwriter. Below my thoughts on the two films - and you can also watch them in full:

Man Hunt (1941)

German filmmaker Fritz Lang had fled Germany in 1933 - and went on to make a series of films in Hollywood that were clearly created to infuriate the Nazi regime. While essentially telling the original story, Man Hunt departs considerably from the novel and, unfortunately, not in a good way.

It gives us an entire first act, with a lengthy and entirely civil conversation between protagonist and antagonist, that takes us all the way to the first act climax when our hero is dropped off the cliff. And whatever the henchmen/torturers have done to our hero (who does have a name in the film) is barely worth mentioning, aka fingernails intact. The reason? Hollywood was worried that the Nazis were portrayed as too evil. Hence the torturing was not shown and its results are minor at best.

Then we’re treated to your typical Hollywood treatment, i.e. “let’s give them something relatable”. The entire second act has little to do with the novel - even if it does follow the same trajectory. First there’s the kid (Roddy McDowell in an early role) as a cabin boy with goofy dialogue and then there’s a female romantic interest - both have nothing to do with the novel and really, really do the story a disservice. Alas, Hollywood, I understand the rationale.

The thing that forces the protagonist to go into hiding in England, the killing of a spy, happens very early in the novel - in this film is comes as the second act climax, two thirds into the film! All of everything that makes the novel so fascinating - the building of the burrow, the way our hero makes it a home, the cat, every detail - all of that is entirely cut. There is simply no time because so much has been squandered on a female character that has nothing to do with the story to begin with. I can only assume that Lang was pressured to insert a female “co-lead”.

There’s one pretty cool thing Fritz Lang did with his film - it was his way of giving the Nazis the finger, and to put a definitive element of fear into Hitler himself. In the novel, our hero tells us that he’ll go back to Germany to finish the job. In the film this is far more specific. We see him having enlisted in the army, then jumping from a plane over Germany without permission, his rifle firmly tied to his body. The narrator tells us, as the protagonist descends from the sky:

“And from now on, somewhere within Germany, is a man with a precision rifle and the high degree of intelligence and training that is required to use it. It may be days, months, or even years, but this time he clearly knows his purpose and, unflinching, faces his destiny.”

Finally, Walter Pidgeon is entirely wrong as the Rogue Male - it is something you’ll know if you’ve read the novel - and it is something you’ll see when you see Peter O’Toole perfectly becoming the Rogue Male in the second adaptation.

Rogue Male (1976)

The 1976 Rogue Male adaptation was made for television by the BBC. Novelist Geoffrey Household (seen below with Peter O’Toole during the shoot) made it clear that, even though unnamed in the novel, the target had always been Adolf Hitler. Household said that

“Although the idea for Rogue Male germinated from my intense dislike of Hitler, I did not actually name him in the book as things were a bit tricky at the time and I thought I would leave it open so that the target could be either Hitler or Stalin.”

Now Peter O’Toole, I mean seriously, what hasn’t he done, right? As amazing and charismatic an actor as they come … and the man did not pick and of the big movies as the personal favorite of all of his movies, he picked Rogue Male, he picked this TV production. In this interview he says:

“Put Lawrence in a niche, by all means, that’s where he belongs. But Rogue Male is my special heart-favorite.”

This film closely follows the book and the first five minutes are intense. With Hitler and crowd outside the house - and the protagonist setting up his shot. He pulls the trigger - and click. The chamber was empty, as he knew it to be. Then he fills the chamber and sets up for the kill shot - no ambiguity about it here. He clearly wants to kill Hitler.

And here’s the one thing I don’t like about the filmmakers’ choices - they keep giving us flashbacks of a woman (clearly the woman he loved), tied up at a post, facing a firing squad. But that really is a minor quibble compared to everything else. In this film, after he’s caught, there’s no hiding the cruelty, the torture, the harshest brutality he suffers at the hands of the Nazis.

In this film, he is thrown over the cliff before long and the first act is the escape of a physically broken man from Germany - there are shortcuts from the novel that the adaptation needs to make, but these are coherent and entirely in keeping with Household’s tale.

While Fritz Lang’s film wasted half the film with a very dissatisfying female plot element, here our hero has to kill his pursuer at midpoint of the film - which makes the need for his going underground urgent. And this means that the heart of the film, the going - literally - underground, gets all the time it needs and deserves. There’s the relationship with the cat, the chases, the farm, getting wounded - here the foe is decidedly stronger (as in the novel). Long story short, it’s the 1976 version over the 1941 version by a mile.

The late sequel

Household wrote his sequel to Rogue Male late in life: Rogue Justice was published more than forty years later, in 1982. It does what the original did not do, it reveals country, target - and the name and history of our protagonist - and that in itself destroys some of the special charm and mystery that was woven into the original story.

In addition, where the original is more and more zeroing in, until protagonist and antagonist are at a stalemate just a few feet apart, this sequel rambles across Europe and beyond. There are some enjoyable moments of danger and friendships - but overall it doesn't come anywhere near Rogue Male.

There is, however, the ending of Rogue Justice. It is very special, a mythical, ambivalent ending that suggests an epic conclusion to the hero’s life. I won’t spoil it, of course! I can assure you, if you’ve read Rogue Male, you won’t be particularly thrilled by Rogue Justice, but you’ll enjoy it well enough, because you get to spend some more time with our hero.