Rambling notes about systemic racism, then and now

I usual write about writing, screenplays, novels, experiences, history, that sort of thing. Today it's something a bit different. If you're Caucasian, like me, come along.

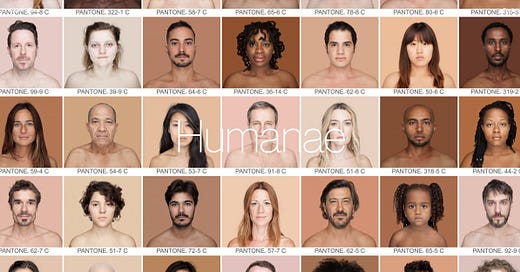

With her global Humanae project, photographer Angélica Dass shows that NOT ONE SINGLE PERSON IN THE WORLD is black or white – we're all shades and mixes of this and that. We are, first and foremost, members of the same species.

Well, she’s right, of course. And efforts like hers have helped to bridge divides and narrow gaps and open eyes. There's all of that on one side – there's well-doing and well-meaning and well-intending and there's no doubt some progress, too … and yet, I keep wondering. Below the surface, how much has really changed?

It is easy to say, as an individual, that "I would never discriminate" – or as a company, "we have a zero-tolerance policy." There's all of the abhorrent conscious racism on one side, and then there's ocean-deep unconscious racism. I won't go into what makes a racist and what is 'just' racist behavior. You know who you are, I know who I am – we should pay attention to the way we live our lives.

One of the old Greeks said that an unexamined life is not worth living. 'Know thyself,' they said – and yes, that should be the maxim. For us to NOT go through life without paying attention to who we are, what we do and think – for us to always examine why we do what we do and think what we think. Most of us basically do try to be decent human beings, right? Harm no one – another nice maxim. And I've always thought of myself as someone with a wide-open mind – and always entirely comfortable with being open to new things, new thought worlds – in the knowledge that I don't know, and will never know, most things.

And then there was George Floyd. And there shouldn’t have to have been a George Floyd and a Black Lives Matter movement. Where the hell had I been when Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Stephon Clark and Breonna Taylor died? Where was my mind then? Was there simply not enough noise for my white mind to be affected enough to start paying attention? Of course I knew what was going on – we all did, we all do. But what could we do, right? And so I went on with my life and the next black person dies, and the next … and the next.

There were many more before Eric Garner – I know that, you know that. Remember Rodney King in 1991? Here’s original footage from what was done to him by LA police officers. Nobody wants to watch that – nobody even wants to believe that a group of men in power could act that way toward another fellow human being lying down. I can’t blame you for not wanting to watch it.

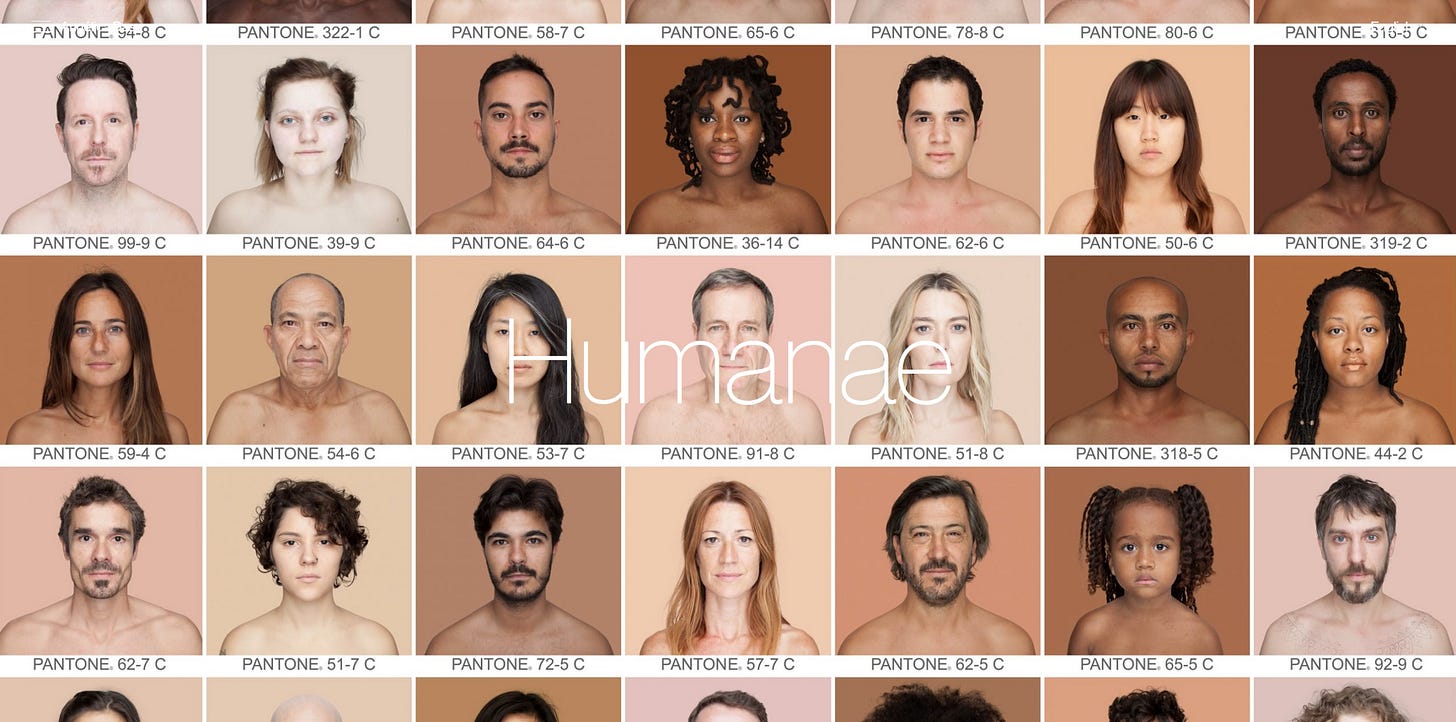

We also know about slavery. While 1619 was the start of slavery in the future United States with the arrival of the first Africans in Virginia, slavery goes further back, much, much further. We know of white man’s subjugation of indigenous peoples, most often of people with various shades of color. We know of colonialism, we know of the crusades, know of the Spanish conquistadores. The British were a busy colonializing lot – but so were the French, the Germans, Italians, Dutch, Portuguese, Belgians and many more.

No doubt some will want to point to times when African tribes subjugated African tribes, and other examples where people of color acted just as white people. First, that wouldn’t make it any better. Second, the scale of this argument is massively tipped in favor of the misdeeds of white people. But I digress, and I will likely continue to digress – because once you start paying attention, once you start walking that road, you come across countless intersections that show you yet another horrid picture of white man’s humanity gone wrong.

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd was murdered by police. Somehow, the outcry was louder than ever before – loud enough for me to hear. Loud enough for the world to take notice. Loud enough for every company to stand up and to earnestly declare that they had zero tolerance for racial discrimination. Many statements, well-meant, no doubt. As for me, I did a bit of soul-searching and realized that I really hadn’t done anything, that I really knew nothing. It’s always easy to say that one can’t know everything – I, too, say it. But what I’m struggling with is that this is injustice and inhumanity that’s been staring me in the face for so many years, and I’ve ignored it. Other than watching a few movies and having a basic grasp of history, I knew nothing and went on with my life with the faint glimmer of hope that, heck, things were slowly getting better for black people, too.

Are they? Are they getting better? As we listened to Black Lives Matter activists, as racism became a hot topic everywhere, I realized that it was nicely served to us in bite-sized snacks. An article here, a podcast there – lots of meaningful panel discussions, lots of people with insight and care and passion explaining what was important and how things could improve. But I noticed that nothing changed – nothing. After all, what could change? The right laws and the right company policies are in place. Change, improvement, has so much to do with our inner workings – it is up to you, to me. The thing that stayed with me most from those talks I listened to was no one particular insight – but a heartfelt frustration. More than one black speaker expressed that they were getting sick and tired of explaining to well-meaning white people what they experienced on a daily basis and why they felt the way they felt. Those frustrated speakers said,

‘If you really are interested, then invest the time, start learning.’

So I began. I realized I had read just about zero books about black lives – whether fiction or non-fiction. I knew OF black authors – but of the myriad of books that have given me countless worlds and characters, just about none were from black authors. I started not with well-known names such as Frederick Douglass or James Baldwin, but instead picked ‘She Would Be King’ by Wayétu Moore. It may have been an odd choice, but it brought me right into the heart of slavery – in ways that were both gruesome and supernatural.

It didn’t just illuminate the loss of home – and life in bondage in the United States – but also taught me about the American Colonization Society – a society that thought that black people would have better chances for freedom and prosperity back in Africa – in a place that would eventually become Liberia. Again, well-meaning white people began that society. But just imagine – free black people in the northern states were now told that they should go off, back to Africa, to find better lives there. They had been in the United States for generations and had no connection with Africa. They had no history, no family, no language, not even a place with regard to Africa. One reason for funding this society, and the travel of black women and men back to Africa, was this: White people were complaining about an increasing number of free black people taking their jobs.

I stuck with fiction and next read Colson Whitehead’s ‘The Underground Railroad.’ Whitehead gives readers an alternate history, of sorts. His underground railroad is an actual system of tunnels and railroads, where the real underground railroad was a network of secret routes and people who helped slaves make their escape to the free states up north.

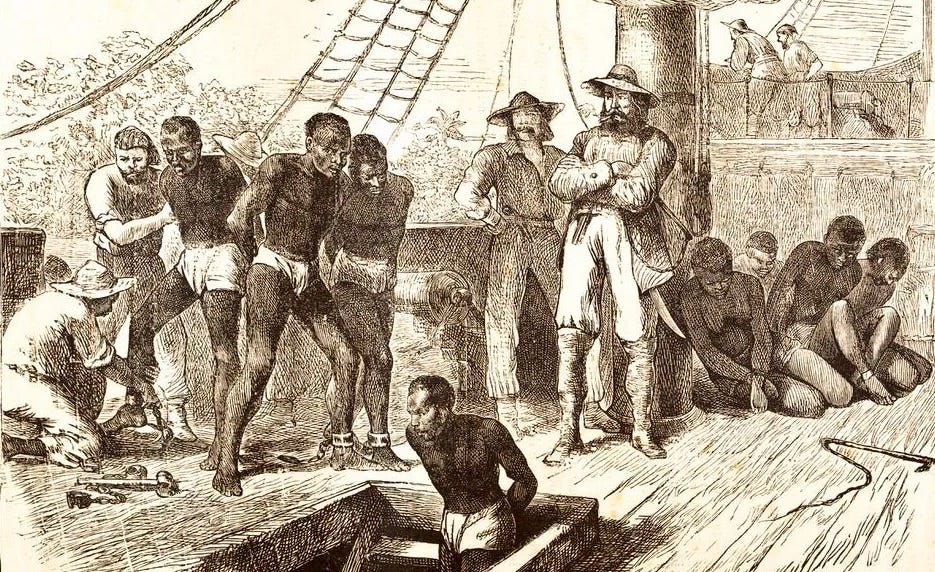

On her journey, the protagonist experiences more than a few of the horrific experiences slave owners had in store for black people. Among them the slave catchers and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 – a law that meant that, even in free states, slave catchers could operate with the power of the law – and officials and citizens had to cooperate. Doing the right thing, aiding a fugitive slave, was now illegal – it could land you in prison and being fined. On the other hand, those capturing runaway slaves were given a bonus. Black people had no right to a trial – slave catchers could therefore easily use their powers to even abduct free black people and ‘return them to their masters.’ Even if one had successfully fled to a northern state, one was no longer safe. White abolitionist John Brown, giving black people refuge, said the following:

“Some of them are so alarmed that they cannot sleep. I want all my family to imagine themselves in the same dreadful condition.”

Brown was captured and executed for a failed incitement of a slave rebellion in 1859. He gave an address to the Virginia court when he was sentenced to death – and it’s been printed in the famed “Liberator” abolitionist paper (a paper of great importance also for Frederick Douglass).

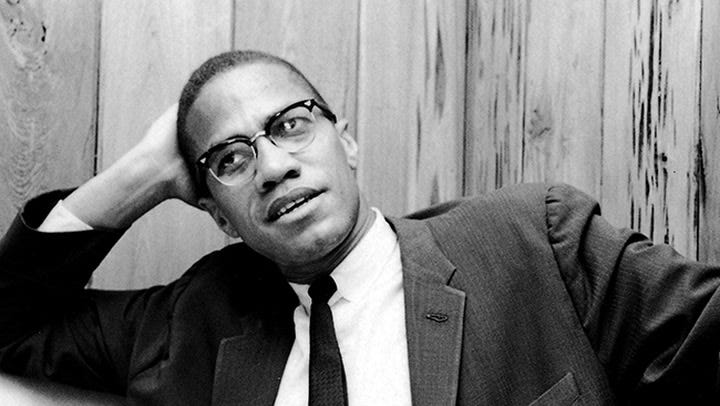

From a great number of black authors, I next turned to Malcolm X. He wrote his autobiography, telling his life’s story to Alex Haley, the famed author of Roots. Talking about Roots – the medium of film has definitely done wonders in many ways. No doubt many more people know about Roots because of the 1977 television series – and even today many, when hearing the name Kunta Kinte, will instantly remember watching the series way back when.

Films are great – lots to experience, lots to learn, lots to feel from the comfort of one’s couch. Who hasn’t watched Glory – the story of the first all-black regiment, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment? Who hasn’t shaken their head at their mistreatment – even the struggle to get shoes, let alone respect or uniforms? Who hasn’t seen Harriet – the biopic about Harriet Tubman and her struggles from slavery to becoming the woman who personally freed more than seventy slaves (via the Underground Railroad system), was a spy for the Union during the Civil War, led 150 black soldiers and saved over 750 slaves? Or how about The Birth of a Nation (2016), about Nat Turner’s slave rebellion, or 12 Years A Slave, Belle, Amistad, Selma, Hidden Figures, Malcolm X and many, many more?

So we watch the movies. Stories that are terrifying, outlandish, illuminating – hard to believe, hard to stomach. Hollywood made them and an increasing number of black directors, writers and actors are finally given a voice. Now. For the longest time, black directors were far and few between. Have we really progressed all that much? We sure would like to think so, wouldn’t we?

Hundreds of years of slavery and then the Civil War that freed black people – what followed was, as we all know, far from a happy non-segregated end of the story. I’m not making this a history lesson, but check out, just to give one example, convict leasing – in the southern United States a new form of slavery. Flash forward to the sixties, the time that officially ended the Jim Crow laws, flash forward to stop and frisk, to the penal system … to George Floyd. Just how much better are things today?

I said I’d digress and so I did – back to Malcolm X. What a life. Watch the movie starring Denzel Washington, by all means. But I’d suggest you read his autobiography. It is illuminating in many ways, from his parents to his conk to crime to the Nation of Islam and all of everything he learned and fought for and against. He, and his mentor Elijah Muhammad and the members of their organization were called any numbers of things – they scared the status quo, that’s for sure.

Malcolm X, by the way, had been born Malcolm Little. When he became an activist, he often spoke of letting go of white things, of stopping to try to emulate and blend in. He dropped his name ‘Little,’ that which he called his slave name. He stopped conking (straightening) his hair. He argued that a living together was not feasible, that white people and people of color should ideally be separated – not segregated, but separated. I hate the idea – it feels like utter capitulation. Us saying that we just can’t live together with a sense of decency, mutual respect and truly equal opportunity. It would be a collective failure of humanity – on every side.

But there’s me hating the idea on one side – and betterment over time on the other. When asked what he thought about improvements that had taken place, about many white people wanting a better future for everyone, about black people making it (in business, in politics, in sports, in the arts), he was very direct, saying:

"I will never say that progress is being made. If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there’s no progress. If you pull it all the way out, that’s not progress.”

Harsh, right? But quite honestly, it resonates. Just because you pull the knife of slavery back an inch or two, doesn’t mean you didn’t inflict the wound, doesn’t make the wound disappear … Again, in terms of time, all of this happened yesterday. Even once the knife is fully pulled, it’ll take much, much more time for the wound to heal. And all of that is not just the wound black people carry with them – it is also a burden, albeit an entirely different one, that white people carry. We always try to make things better – if you ask Malcolm X, he’ll say all the well-intentioned white people pointing out instances of progress here and there, are simply trying to appease their guilt. Do I feel guilty? No, I don’t. Do I feel helpless? Yes, I do.

The so-called “Jim Crow” segregation laws were officially ended in 1965. Before then and since the 1870s (just a few years after the end of the Civil War), former secessionist states mandated the racial segregation in all public facilities. “Separate but equal,” it was officially called – but segregation was enforced and anything for the black community was consistently underfunded and under-maintained. Far from equal, the laws ensured disadvantages of just about every kind for most black people living in the United States – whether it was transportation, or labor, or education – black people were kept down and in place – “separate but equal,” indeed. It took another 100 years after the end of the Civil War, for those laws to finally end.

If the focus of my thoughts seems intensely on the United States, well, it doesn’t just seem that way. I’m aware of what colonial powers did in other parts of the world, the French, the Ottoman, the Belgians (such as the atrocities in the Congo). Injustices to fill countless history books. And even if history was always written by the victors in the past, more and more of it is rewritten to reflect just how much wrong has been perpetrated against so many millions of people around the world. And yes, sure, it wasn’t always white people doing the perpetrating, but, for the most part, that’s what it was. And in the United States, it keeps being put on undeniable display.

Just take the current abomination put on display with the drive to ban books. Among the books that are supposed to be banned from student's eyes are, of course, books that give a frank account of slavery. White parents exclaim that it would upset their children to know the actual history of the United States of America. Or take the made-up outrage about critical race theory … it's infuriating, troubling, saddening … and again it shows that the monster of racial division lurks just barely below the surface. It's right there. And it continues to fester.

Invariably, some people will shout the names of Barack Obama and/or Kamala Harris to highlight ‘just how far we’ve come’ … but activists like Malcolm X decried the highlighting of so-called successes as appeasement – as lulling everyone into a false sense that things were going in the right direction and that, eventually, everything would be equal, everything would truly be fair. But whether it is education, or healthcare, or housing, or employment, or wages, or the law – people of color are still disproportionally getting the very, very short end of the stick.

Today there’s discussion after discussion about systemic (or institutional) racism (follow the link and you’ll be going deep on a whole lot of systemic racism) – about an entire system not just flawed, but purposely rigged. Likely, if you’re in an economically better position, you’ll be saying that things have improved. From a loftier place, things may indeed look better. But then I recall the infuriatingly telling story of Oprah Winfrey, in Zurich, trying to buy a pricey bag. The shop assistant didn’t want to show it to her, saying that it was too expensive for her. The woman didn’t know that she had the one and only Oprah in front of her. All she knew was that she was a saleslady in a high-end store – and that a black woman wanted to take a closer look at something that, in her mind, that woman couldn’t possibly afford … the white mind, the black experience … again, just how far have we really come?

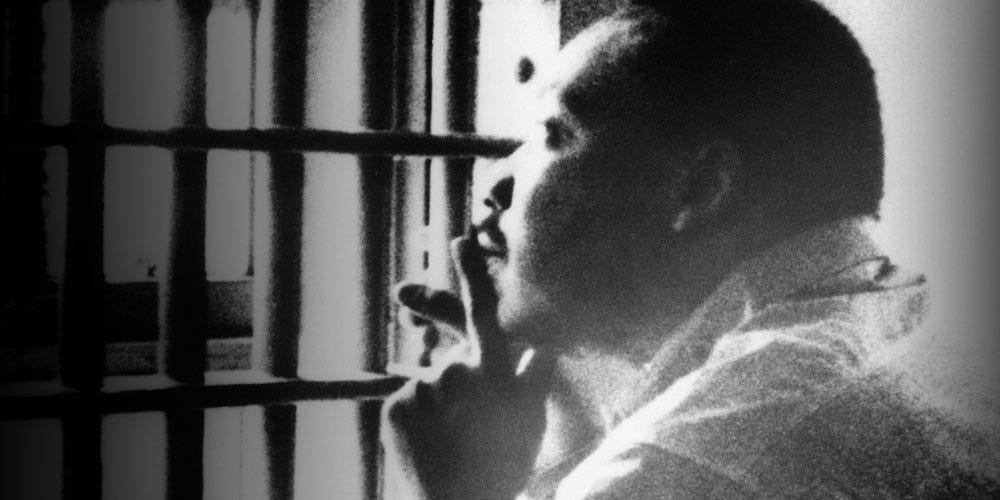

A word about moderation - about moderates - about working within the law, as opposed to standing up for justice ... In 1963, in the midst of the Birmingham, Alabama, protests, Martin Luther King Jr. was in jail. While he was in prison, eight well-meaning white clergymen from Birmingham wrote an open letter that black protestors should stop protesting and instead focus on using the courts - act within the law - to improve their situation. It led to MLK to write, from his prison cell, an open letter in reply. It's not just well worth reading - there's really no way around it if you're interested in the topic. In the letter he wrote the famous: "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere." But he wrote more, so much more - here is what he wrote about the well-meaning white moderates:

"I must make two honest confessions to you, my Christian and Jewish brothers. First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro's great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen's Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to "order" than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: "I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action"; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man's freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a "more convenient season." Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection."

'Negative peace' or 'positive peace' - in this quote alone there’s lots to think about. You can find the full letter here and below is an audio recording of Martin Luther King Jr. reading his own letter.

On December 4, 1969, a twenty-one-year-old black man was assassinated – by the police, with the blessing of the FBI. Fred Hampton was as fervent as could be, and he was the deputy chairman of the national Black Panther Party. That young man was vocal, eloquent, in-your-face – and he created a Chicago coalition (the Rainbow Coalition) of disenfranchised people – bringing people both black and white together to form an alliance. The FBI identified Hampton as a threat. They subverted Hampton’s efforts, placed a mole in his inner circle – and then, in December of 1969, he was drugged, shot and killed.

It was a raid of his apartment in the middle of the night. The people inside were asleep. The police riddled the apartment with more than 90 bullets – the people on the inside fired once (a shot that hit the ceiling). There were the wounded and the dead, among them Fred Hampton himself, shot and killed (with two bullets to the back of the head). He had been deep asleep with a sedative he had been slipped. His girlfriend was there, close to nine months pregnant. Police spun the story, the deaths were considered justifiable homicides – it was the end of the Fred Hampton story as far as they were concerned. How it was spun, and how the truth was pointed out, is on display in this 26min documentary: Death of a Black Panther: The Fred Hampton Story.

The aforementioned mole was William O’Neal. From 1956 to 1971 the FBI ran COINTELPRO, a program that consisted of a series of covert and illegal projects to ‘infiltrate, discredit and disrupt’ any number of what were deemed ‘disrupting domestic American political organizations.’ Not surprisingly, civil rights movements and anyone aiming for greater race equality (like Martin Luther King, the Nation of Islam, the Black Panthers) were high on the COINTELPRO list. So the FBI approached O’Neal and offered him a deal to get rid of his felony charges – plus be paid by the FBI for his services. And so he did.

By the way, Hollywood produced an excellent feature film about both William O’Neal and Fred Hampton, Judas and the Black Messiah. After Hampton’s assassination, O’Neal’s role remained secret. When it was revealed, he entered the witness protection program. In the late 80s he agreed to be interviewed by PBS about his role (here’s the full interview) – after the interview premiered, O’Neal committed suicide.

What do I make of this story? Why am I mentioning it? To me, it shows how the status quo (in this case the FBI) did all it could to maintain that status quo – with no regard for anyone ‘other.’ They used and abused, in this case William O’Neal, to sow discontent, to disrupt and to ultimately destroy. Malcom X and others were decried for using the words ‘by any means necessary’ … they didn’t – but those defending the status quo most certainly did. O’Neal carried his guilt with him – a rucksack of deceit strapped on his back by the FBI – until he could carry it no longer. That suicide took place in early 1990 – more than thirty years ago. Surely things have improved since then, right? But remember the opening of this article, the mention of Rodney King in 1991 – and the many names that followed since, until the world cried out for George Floyd because it was entirely impossible to NOT see?

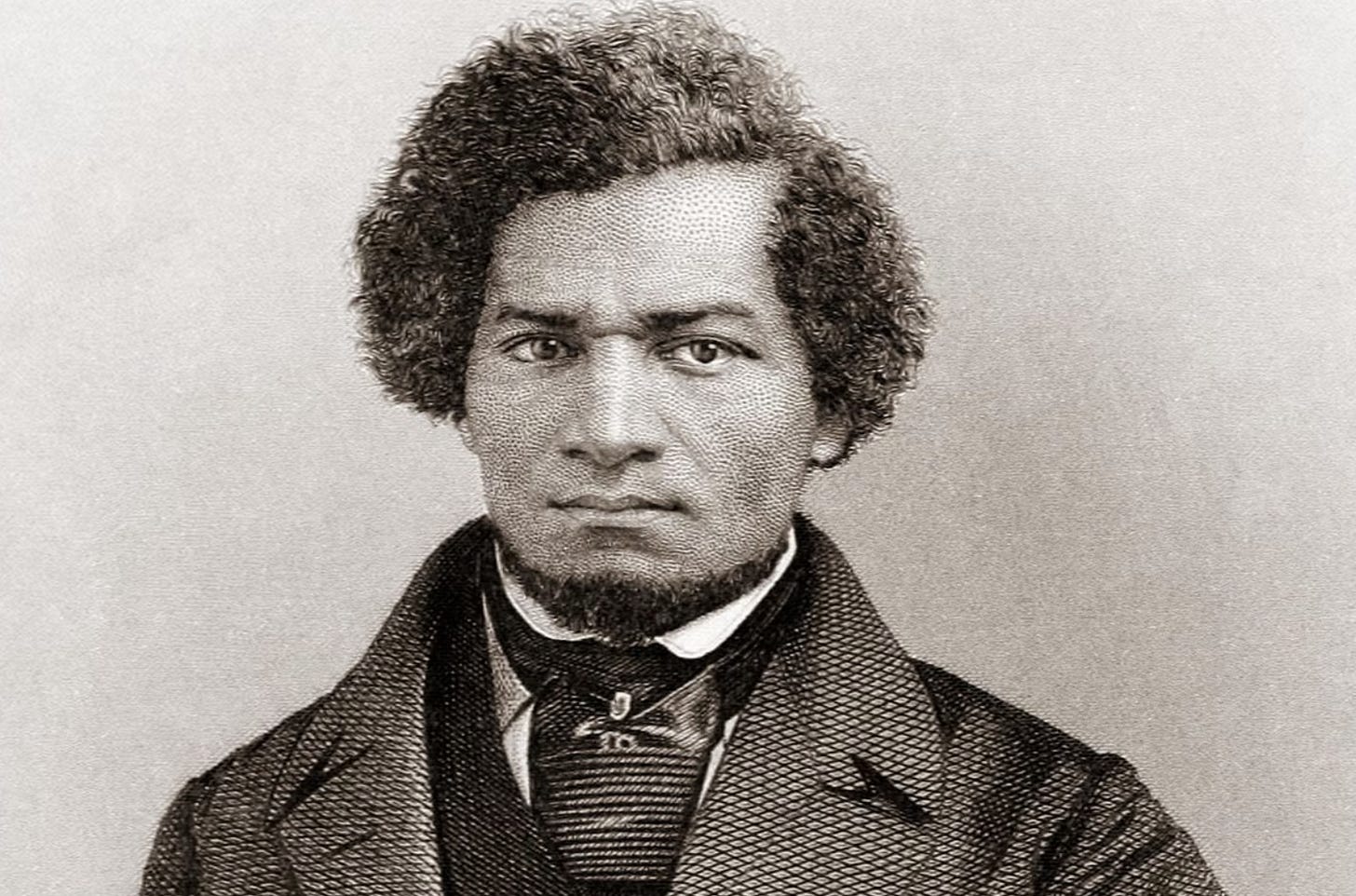

I wasn’t done reading. Frederick Douglass published his first autobiography in 1845: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (here it is online on Gutenberg.org). His story is the story of many who grew up in bondage, eventually broke free and escaped to the north – and learned to discover that racism continued far beyond the bonds of slavery. As I was reading it, I couldn’t help thinking that we would break – you and me and everyone – if we were to be thrown into bondage.

To be owned, to grow up with nothing, to own nothing, to be whipped for a word, or a need, or an error. To be separated from one’s family, one’s mother. To be used, abused, raped, mutilated, torn, bought, sold – to be kept by simplest means, to sleep on the ground, to have nothing against the cold, to be fed mush from a trough, to be forced to smile, to be asked to love your master’s religion – to be kept ignorant of the world, of even the mere hint of learning. Douglass was lucky and industrious – with the little he had, he learned to read – and then tried to teach others. And when he was finally free, he built on his skill and became, to this day, one of the most renowned abolitionists.

Before George Floyd, I knew Frederick Douglass’ name. Period. Now I know a bit more. I’m glad I know a bit more. But why did it take me so long to feel the need to want to know more? Because there was no need. I’m white, things are good – for all intents and purposes, things are just peachy. I’d have to disguise myself to receive the mistreatment Oprah Winfrey got when she entered that aforementioned store. With all of everything she’s got, she still also carries all of that history, all of that bias, all of that systemic racism, with her wherever and whenever she interacts with white people - simply because of the color of her skin.

For all of the blood-stained centuries that have come and gone, where are we today? A world that seems more polarized than ever before – a world where black people die and you’ll have a bunch of white people holler with all the righteous indignation they can muster: “All lives matter!” We are NOT in a good place, we are FAR from a just place. And I’m a white dude, rambling. I know a bit more now, sure. I’ve made a bit of an effort to pay attention. Big deal.

I may have an inkling of knowledge of what things were like and what the challenges were then and are now. But I’ll never be impacted by "the look”, simply for having a darker skin. Please watch the below video – it’s less than two minutes long. It’s telling – but aside from what they were trying to highlight with this video, it infuriated me when I got to the end of it. Spoiler – the black man in question turns out to be a judge. The whole message of the video is undercut, I think. You don’t have to be anyone of particular standing to deserve equal amounts of decency and respect.

Frederick Douglass would have been a good place to stop – but, while I was reading, I was thinking, of course. All of everything I read and saw and heard told me, tells me, that we’re nowhere near where we claim we want to get to. I keep wondering – what can we do? What can I do? What can governments do? There’s Affirmative Action with all of its arguments pro and con – racial quotas … even the term shouts of a world of wrong. And yet, if betterment didn’t come about by any other means? And don’t get me started on the Supreme Court.

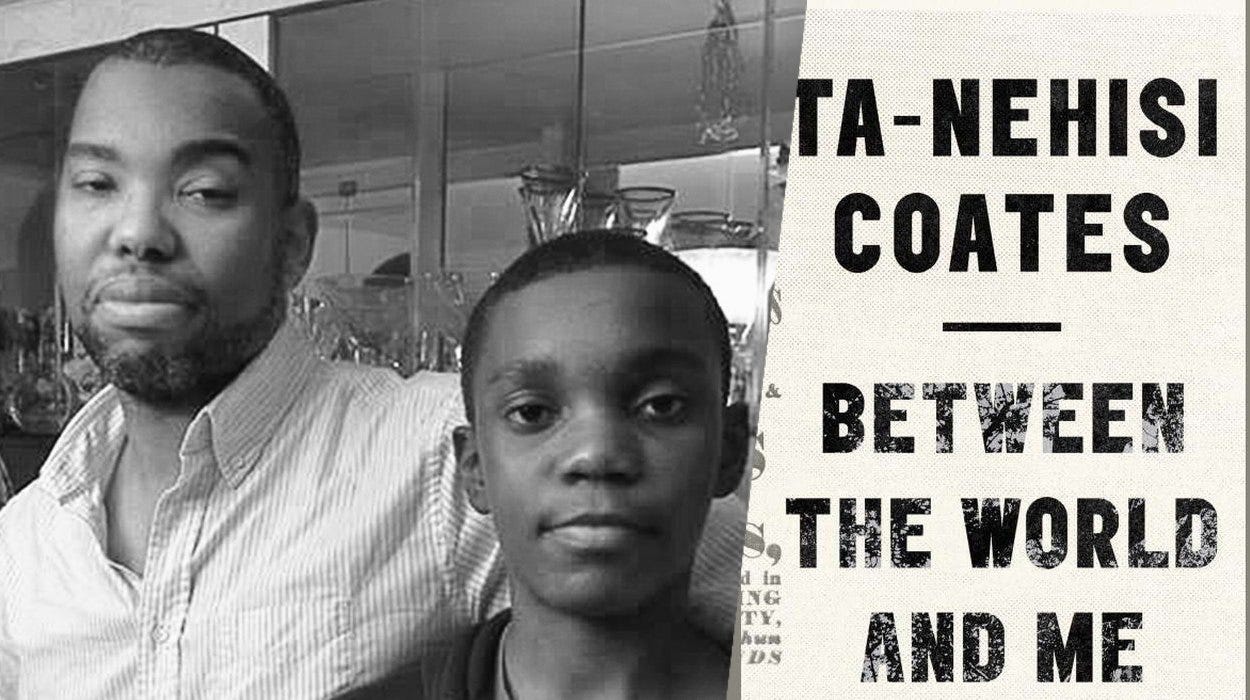

Ta-Nehisi Coates, born thirteen years after me, in 1975, is a well-known journalist and author. Writing for The Atlantic, he wrote about social issues, especially with a focus on African Americans and white supremacy. And he wrote about the idea of Reparations – his was an article published in 2014, The Case for Reparations (here the article directly at The Atlantic). I think that singular article makes so much so clear – showing so much of why there is such a discrepancy between the white and the black experience. And yes, it makes the case for reparations.

A large chunk of the white population is against reparations – any form of compensation for all the wrongs – a large chunk of the black population supports reparations. We often like to say that things aren’t as simple as black or white, that there are shades of differentiation, that there are nuances … but when it comes to pro or con reparations, the matter really does seem pretty clear-cut black or white. Following Ta-Nehisi Coates’ article, a conservative journalist published an article arguing against reparations. He wrote: “The people to whom reparations are owed are long dead.” But that is simply not the case.

We don't grow up in bubbles, we don't live in a vacuum (even though it seems that many people would very much like that), we are the sum of our experiences as gained from our interactions, our learnings, our frictions made in a very real world, a world that is filled with history and biases and sentiments. Our experiences are formed from an onslaught of everything that happens within and without us – and that includes our parents, our elders, our friends, our acquaintances, their experiences, their stories.

What slavery did is not dead, is not in the past – it is alive in the everyday experiences of those alive today. The idea of reparations isn’t some lofty ideal. Germany paid Israel’s government reparations for fourteen years after the war. And especially when seeing just how much has been done – to this day – to massively tip the wealth balance in favor of white people (to give an example – learn about redlining), reparations would not just acknowledge the horrific wrongs, but also begin to make material amends toward a world that is more fairly balanced.

Five years later, in June of 2019, Coates was asked to testify at a House hearing – he did so – here’s the full text of his opening statement. Personally, I’m reminded of what I’ve mentioned earlier in this article – white people like things explained to them by black people. I get that some hearings help to give further prominence to a particular issue, and I’ve no doubt that Ta-Nehisi Coates took the time to be there for that very reason. But, frankly, all anyone had to do – and has to do – is take the time to actually read his article about the case for reparations.

It’s all there. It really is all there for anyone willing to take the time, for anyone willing to see. Read it, especially if you’re white, read it. As for me, I’ve continued reading. Next I it was Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me – a very personal reflection, written in the form of a letter from the author to his son. This should be, for white people as for black, required reading. Here's Coates in a one-hour interview that focuses on that book - and ever so much more.

There you are, there I am – that's where I am right now. White people wanted segregation, Malcolm X wanted separation – and I wish I'd see a path now, a path to end systemic racism. The one thing I could see would be a united black front – not a Black Panther Party – but a Black Party, a political party that would bring its full power to bear as part of the political process. There would be a great deal of power there … and lots of people say that this is also something that the status quo is always striving to stop from happening.

It's so much easier to keep the status quo if you can keep distracting and dividing your opponents (something that's become particularly easy in our social media times). But that's the outer world – a political party might work. Reparations would work, would lead Americans to reckon with their past, to come to terms, to find truth, to let go of guilt. But it would undeniably also trigger another wave and rise of white supremacy movements. And that's why I'm still so frustrated. It is, it remains, all of it, a deeply engrained matter we have to work out within ourselves. I see a great deal of acknowledgement and well-meaning – but I don't see a great deal of actual societal change. What will it take for us (our human race, our society, generations to come) to stop making instant judgements based on skin color? I don't know. I don't see it, I don't see the path.

I've now read Martin Luther King's autobiography - written by Clayborne Carson ... I wonder, I really do wonder - what would he say? What would he say, sixty years after the civil rights movement, after the freedom rides, after the bus boycotts, after the beatings and imprisonments and murders of that time, after that culmination, that supposed victory, of the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965? What would Martin Luther King say?