"Great scripts are forged in battle..."

The title's quote continues with "... and it's not a battle that either should win." Collaborative battles between screenwriters and directors couldn't be more important.

Hollywood is a business. The factory needs to produce and the factory does produce - sometimes (often) faster than it should. Most stories need time, quality time, to become good stories, let alone great stories. Too often, collaborative battles are not fought, instead ‘creative differences’ are cited and a next screenwriter is brought on board.

Gladiator and Elizabeth: The Golden Age scribe William Nicholson talked about this during a BAFTA screenwriter’s lecture a bit more than ten years ago, “We have a chance of rescuing the film process from this (Hollywood) degradation” of hiring and firing screenwriters, of having a half dozen screenwriters working on a film... Personally, I don’t think we’ll be able to change the factory - it needs to run, it needs to crank out product. But we can and must fight for every individual story we’re working on.

“Great scripts are forged in battle, and it’s not a battle that either side should win.”

I’ve dug around the world wild webs and have found where this quote actually comes from. It stems from an article written by James Park for a film quarterly publication called Sight & Sound (volume 59, 1990). While the article focuses primarily on the (perceived) poor quality of British films at the time, I find the article fascinating because of a good number of valuable insights by screenwriters like the aforementioned William Nicholson (at the time early in his stellar career). The article also quotes my own literary agent, Julian Friedmann, a few times. I’ll add the article’s pages below, as well as a transcript for easy reading - well worth the read, I can assure you. Lots of insights and good thoughts about what struggles and challenges between writers and directors - and about how matters could be improved and rebalanced for better collaboration.

Back to the quote - I love it. William Nicholson rightly argues that we should insist on being trusted to get the script right. He says - and I commend him for his passion:

“I’ll go on rewriting until the cows come home. I’ll find an answer to your problem - but do not rewrite it yourself and do not get in another writer. I’m fallible, I’ll get it wrong. Tell me and I’ll fix it - but it’s got to come through my head.”

We may be tossed off a project regardless of what we say or do - a producer may choose a different writer for any number of reasons, but we should always try our hardest to stay on board - we owe it to the story. I’ve often enough been in situations where I just wanted to walk away, where that inner siren tempted with a soothing “You don’t need this hassle. It’ll all be so peaceful again, if you just call it quits.”

We’re not quitters - we’re screenwriters. We have decided to be in this impossible business - we were nuts to begin with. We will not walk away from our stories, from our characters, from those fictitious worlds of ours that are as real to us as our very lives - we will not walk away without a fight.

Those battles mentioned in the title, they’re worth fighting, every time, with every draft, at every step. Because those fighting people want to make the best film possible. And, just like William Nicholson, we’re all fallible. We all make mistakes, we need to be challenged, we need to be forced to argue on behalf of our decisions. Every such challenge improves the script, makes it more powerful, maybe even makes it - great.

Here the aforementioned article’s 5 pages as images. If you’re reading on your smart phone, then scroll to find the transcript for an easier read.

Transcript: JAMES PARK ARGUES THAT THE PROBLEMS FOR BRITISH FILMS START WITH THE SCRIPT

The old line that a poem is never finished, only abandoned, applies also to film. There's no limit to how far you can alter, change or improve a film. But the first draft is probably the area where the writer does impose a large amount of the finished shape of the film. The work you do after that is detailed, rather than structural. In my experience on seven scripts that have gone to filming stage, there has not been a major rethink, going back to square one. WILLIAM BOYD (Stars and Bars, Mister Johnson, Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter)

The ideal situation is that a director is going to come in, respect your work, respect your intentions, agree with them, and give it wings, make it better. MAGGIE BROOKS (Loose Connections, Heavenly Deceptions)

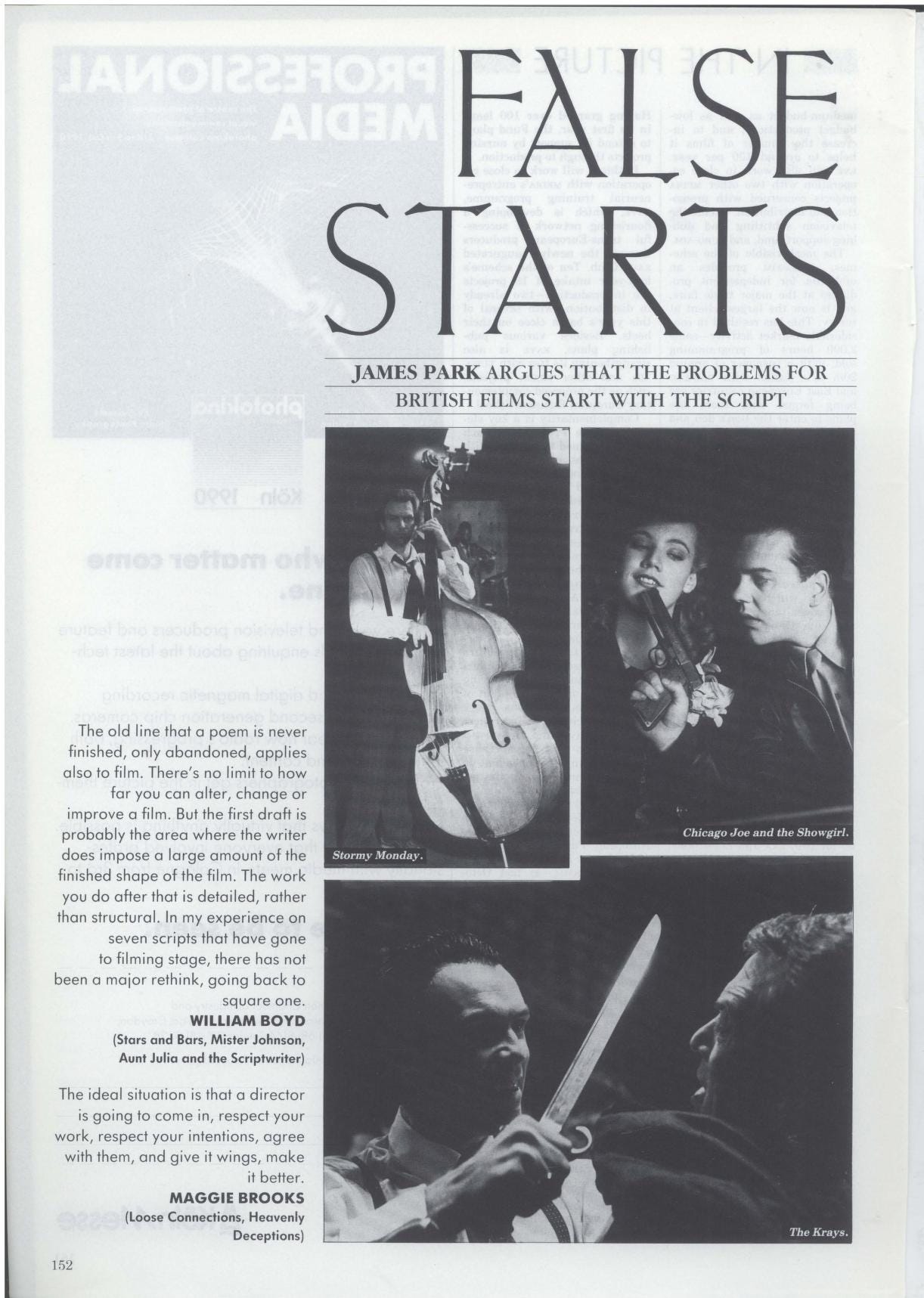

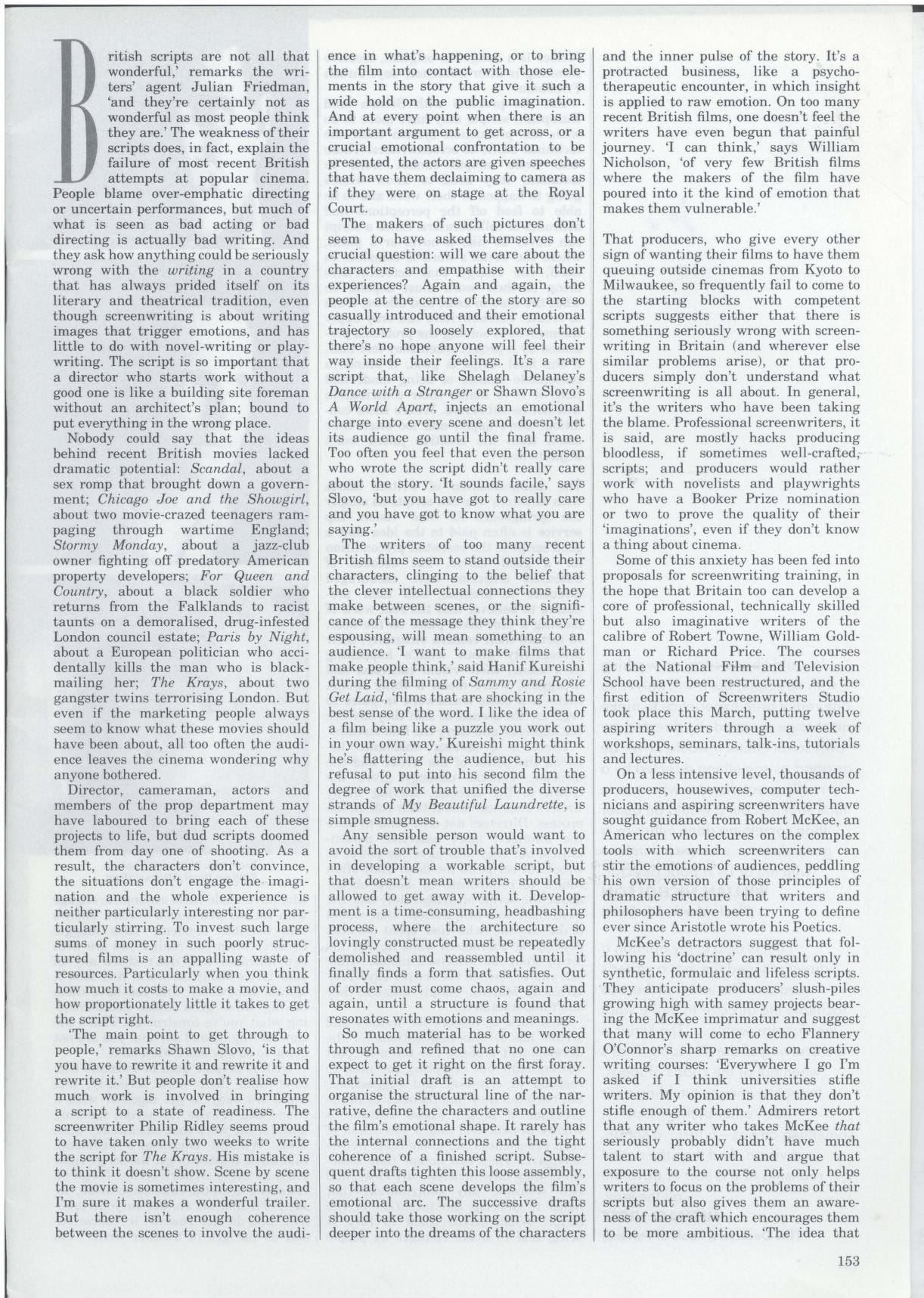

British scripts are not all that wonderful,’ remarks the writers’ agent Julian Friedman, ‘and they’re certainly not as wonderful as most people think they are.’ The weakness of their scripts does, in fact, explain the failure of most recent British attempts at popular cinema. People blame over-emphatic directing or uncertain performances, but much of what is seen as bad acting or bad directing is actually bad writing. And they ask how anything could be seriously wrong with the writing in a country that has always prided itself on its literary and theatrical tradition, even though screenwriting is about writing images that trigger emotions, and has little to do with novel-writing or playwriting. The script is so important that a director who starts work without a good one is like a building site foreman without an architect’s plan; bound to put everything in the wrong place. Nobody could say that the ideas behind recent British movies lacked dramatic potential: Scandal, about a sex romp that brought down a government; Chicago Joe and the Showgirl, about two movie-crazed teenagers rampaging through wartime England; Stormy Monday, about a jazz-club owner fighting off predatory American property developers; For Queen and Country, about a black soldier who returns from the Falklands to racist taunts on a demoralised, drug-infested London council estate; Paris by Night, about a European politician who accidentally kills the man who is blackmailing her; The Krays, about two gangster twins terrorising London. But even if the marketing people always seem to know what these movies should have been about, all too often the audience leaves the cinema wondering why anyone bothered.

Director, cameraman, actors and members of the prop department may have laboured to bring each of these projects to life, but dud scripts doomed them from day one of shooting. As a result, the characters don’t convince, the situations don’t engage the imagination and the whole experience is neither particularly interesting nor particularly stirring. To invest such large sums of money in such poorly structured films is an appalling waste of resources. Particularly when you think how much it costs to make a movie, and how proportionately little it takes to get the script right.

‘The main point to get through to people,’ remarks Shawn Slovo, ‘is that you have to rewrite it and rewrite it and rewrite it.’ But people don’t realise how much work is involved in bringing a script to a state of readiness. The screenwriter Philip Ridley seems proud to have taken only two weeks to write the script for The Krays. His mistake is to think it doesn’t show. Scene by scene the movie is sometimes interesting, and I’m sure it makes a wonderful trailer. But there isn’t enough coherence between the scenes to involve the audience in what’s happening, or to bring the film into contact with those elements in the story that give it such a wide hold on the public imagination. And at every point when there is an important argument to get across, or a crucial emotional confrontation to be presented, the actors are given speeches that have them declaiming to camera as if they were on stage at the Royal Court.

The makers of such pictures don’t seem to have asked themselves the crucial question: will we care about the characters and empathise with their experiences? Again and again, the people at the centre of the story are so casually introduced and their emotional trajectory so loosely explored, that there’s no hope anyone will feel their way inside their feelings. It’s a rare script that, like Shelagh Delaney’s Dance with a Stranger or Shawn Slovo’s A World Apart , injects an emotional charge into every scene and doesn’t let its audience go until the final frame. Too often you feel that even the person who wrote the script didn’t really care about the story. ‘It sounds facile,’ says Slovo, ‘but you have got to really care and you have got to know what you are saying.’

The writers of too many recent British films seem to stand outside their characters, clinging to the belief that the clever intellectual connections they make between scenes, or the significance of the message they think they’re espousing, will mean something to an audience. ‘I want to make films that make people think,’ said Hanif Kureishi during the filming of Sammy and Rosie Get Laid , ‘films that are shocking in the best sense of the word. I like the idea of a film being like a puzzle you work out in your own way.’ Kureishi might think he’s flattering the audience, but his refusal to put into his second film the degree of work that unified the diverse strands of My Beautiful Laundrette , is simple smugness.

Any sensible person would want to avoid the sort of trouble that’s involved in developing a workable script, but that doesn’t mean writers should be allowed to get away with it. Development is a time-consuming, head-bashing process, where the architecture so lovingly constructed must be repeatedly demolished and reassembled until it finally finds a form that satisfies. Out of order must come chaos, again and again, until a structure is found that resonates with emotions and meanings. So much material has to be worked through and refined that no one can expect to get it right on the first foray. That initial draft is an attempt to organise the structural line of the narrative, define the characters and outline the film’s emotional shape. It rarely has the internal connections and the tight coherence of a finished script. Subsequent drafts tighten this loose assembly, so that each scene develops the film’s emotional arc. The successive drafts should take those working on the script deeper into the dreams of the characters and the inner pulse of the story. It’s a protracted business, like a psycho-therapeutic encounter, in which insight is applied to raw emotion. On too many recent British films, one doesn’t feel the writers have even begun that painful journey. ‘I can think,’ says William Nicholson, ‘of very few British films where the makers of the film have poured into it the kind of emotion that makes them vulnerable.’

That producers, who give every other sign of wanting their films to have them queuing outside cinemas from Kyoto to Milwaukee, so frequently fail to come to the starting blocks with competent scripts suggests either that there is something seriously wrong with screenwriting in Britain (and wherever else similar problems arise), or that producers simply don’t understand what screenwriting is all about. In general, it’s the writers who have been taking the blame. Professional screenwriters, it is said, are mostly hacks producing bloodless, if sometimes well-crafted, scripts; and producers would rather work with novelists and playwrights who have a Booker Prize nomination or two to prove the quality of their ‘imaginations’, even if they don’t know a thing about cinema.

Some of this anxiety has been fed into proposals for screenwriting training, in the hope that Britain too can develop a core of professional, technically skilled but also imaginative writers of the calibre of Robert Towne, William Goldman or Richard Price. The courses at the National Film and Television School have been restructured, and the first edition of Screenwriters Studio took place this March, putting twelve aspiring writers through a week of workshops, seminars, talk-ins, tutorials and lectures.

On a less intensive level, thousands of producers, housewives, computer technicians and aspiring screenwriters have sought guidance from Robert McKee, an American who lectures on the complex tools with which screenwriters can stir the emotions of audiences, peddling his own version of those principles of dramatic structure that writers and philosophers have been trying to define ever since Aristotle wrote his Poetics.

McKee’s detractors suggest that following his ‘doctrine’ can result only in synthetic, formulaic and lifeless scripts. They anticipate producers’ slush-piles growing high with samey projects bearing the McKee imprimatur and suggest that many will come to echo Flannery O’Connor’s sharp remarks on creative writing courses: ‘Everywhere I go I’m asked if I think universities stifle writers. My opinion is that they don’t stifle enough of them.’ Admirers retort that any writer who takes McKee that seriously probably didn’t have much talent to start with and argue that exposure to the course not only helps writers to focus on the problems of their scripts but also gives them an awareness of the craft which encourages them to be more ambitious. ‘The idea that McKee is a danger to original, creative thinking is utter nonsense,’ says Julian Friedman.

I would like to carry on working with directors, but it will only take one really grim experience to make me change my mind. If I directed my own script I think it would never be as good as something directed by a really great director who was in tune with me. But it would be better than something done either by a great director who wasn't in tune with me or by a poor director. WILLIAM NICHOLSON (Shadowlands, Life Story)

Film is also in my opinion a director's medium, not a writer's medium. The writer is there to facilitate the director to make what the director wants ... The script is the evolving of the film idea. That's when out of the chaos of ideas, thoughts, images tumbling over each other in the darkness, something comes —a form, a shape, a vision. And then the actual realising of it is sort of downhill all the way. MICHAEL HIRST (The Deceivers, Fools of Fortune)

But the problem with British (and European) scripts may have more to do with the production system than the technical skills of screenwriters. Those who write scripts cannot work in isolation, they need to know what’s going to happen to their work and to be able to feed off the perceptions and attitudes of collaborators. Since a script can never be like a novel or a poem, where the writer’s work is complete in itself, the energy that screenwriters bring to their work must depend on what the system asks, and allows, them to create. Screenwriters can only apply themselves to solving the problems presented by a project when they feel that, if the final script is good, it stands a reasonable chance of being made and that, if it is made, their contribution will not be subverted. Where those conditions don’t apply, and too often they don’t, then the creative juices won’t begin to flow.

The demoralisation of writers starts with directors who see scripts as simply the springboard for their vision. Lip service is often paid to the idea that a good script is the essential precondition for a good movie, but decades of auteurist criticism have encouraged directors to promise, and their producers to believe, that the real work of making a film takes place on the floor. In fact all their camera virtuosity, their perceptivity about what’s happening in a scene, their visual cadenzas and arpeggios, won’t mean a thing unless there is a basic framework in place to organise the scenes, so that they involve the audience and carry the film forward. There is a serious imbalance between the power of the writer and the director. Critical ideology gives the crown to the director, leaving many writers uncertain about their role in the process. Directors not only tend to have the stronger, more assertive personalities, but they also have the power to wreck the script on the floor. They often refuse to collaborate by being obtuse about the script or deliberately ask the writer the sort of questions that would make anyone who had spent months developing characters want to tear his script from the director’s hands. ‘They ask you to rewrite the script,’ says Troy Kennedy Martin, ‘simply because they don’t understand it.’

This lack of respect for writers and scripts has serious implications for the development process. For the most part writers start out accepting the need to respond to criticism and suggestions, but too often they find themselves in the presence of people whose attitude is wholly destructive; and a succession of such experiences can make them hyper-defensive. They can accept that something they have written isn’t clear, and will welcome any contribution that helps to develop the intention of the script. What drives them to fury is being told to make changes by people who have made little attempt to engage with the script’s deeper levels. ‘There’s this horrible moment,’ says Maggie Brooks, ‘when you realise you are with two nutcases who don’t share any of your views about the work. And then it spirals somewhere, and you have them having these good ideas, deconstructing what you’ve constructed. That’s the time to ring up and say that you are not going to do any more work on it.’

Writers become used to directors who can’t take their work seriously, and think it’s okay to get together with a friend and rewrite the script, ignoring much of the work that has already been done. William Nicholson’s insistence that he be trusted to get the script right could be every writer’s credo. ‘I’ll go on rewriting until the cows come home,’ he says. ‘I’ll find an answer to your problem, but do not rewrite it yourselves and do not get in another writer. I’m fallible. I’ll get it wrong. Tell me and I’ll fix it, but it’s got to come through my head.’

Being paid for what they do can also be a problem. Although there is money available from the National Film Development Fund and the new European Script Fund for producers to fund first- and second-draft scripts, writers remain susceptible to exploitation by producers who think they should write treatments for free, and do further work on a script even when they have only been paid for two drafts. The line will often be that these rewrites are what’s needed to land the requisite cash, which is anyway a rather demoralising process. ‘If the thing is going to be made,’ says David Pirie, ‘there is no limit to the amount of work a screenwriter should put in. But as far as just allowing a succession of financiers, who may or may not put money into the project, to make suggestions, that’s hopeless.’ A writer’s optimism about a film’s financing prospects, and desire to make a script come right, necessarily decreases with each unfinanced draft.

Alternatively, producers deceive themselves into believing that the script’s problems can be sorted out after the money has been raised. This almost never happens. With the money in place, the urgency goes out of the development process, and having a film hurtling towards the starting gate doesn’t encourage anyone to embrace the prospect of pulling the script to pieces and thinking through a new approach to the structure.

All the arguments that have gone on over the years about the respective role of writers and directors assume that somebody must come out on top, and that a work which isn’t dominated by the mind of a single individual isn’t worth anything very much. A recent edition of the South Bank Show , about the collaboration between David Lean and Robert Bolt on a film version of Conrad’s Nostromo , showed the two veterans working together amicably and fruitfully on a script. Neither seemed constrained as to the area in which he could contribute, but Bolt clearly took responsibility for structure and characterisation while Lean thought through the possibilities and difficulties of individual scenes. Then suddenly, as if articulating some deep inner frustration, Lean declared his hope that one day a genius would come who could combine both functions, shaping images and structuring films.

Since the vast majority of writer-directors obviously don’t rate against Ingmar Bergman, Akira Kurosawa or Andrei Tarkovsky, it’s surely time to develop a creative ideology which embraces the fact that collaborative endeavour can produce films much more engaging and interesting than those of a solo auteur. Too many writer-directors see their movies as vehicles for self-expression or soap-boxing, shy away from those elements in cinema that communicate most directly to an audience. The result is that they produce one-dimensional work, made from scripts that haven’t had a chance to breathe or grow, which nobody really wants to see. Only through collaborating with others, and learning to make films that contain contradiction and conflict, can these film-makers realise their own potential.

Collaboration must start from discord. Each collaborator brings to the project their own particular experiences, attitudes and ambitions. One is concerned with the structure that will motivate the succession of images, the other with ensuring that each moment has depth and resonance. It’s only when both are willing to fight for their pitch, finding solutions that satisfy them both, that they will also find a way through to an audience. The forces must be evenly matched to some extent—writers who see themselves as simply handmaidens of a director’s vision aren’t likely to stand their ground. Great scripts are forged in battle, and it’s not a battle that either should win. Where any party ends up with their boots on the head of the vanquished corpse, the result will be a film that is satisfactory only in parts. By putting their two minds together, writer and director can fight their way through to the emotional crux of the story and, in the creative tension between them, can be born ideas and images that go far beyond what either of them could have created on their own.

The more distinctive the writers or directors involved, the more difficult it is to establish that relationship of collaborative trust, and it may be that those sorts of relationships were easier to build within the kind of studio structure that effectively collapsed in Britain at the end of the 1940s. It’s difficult now to imagine an Emeric Pressburger collaborating with a Michael Powell on a series of films over fifteen years.

Decades of director-worship have ensured that no one really takes seriously the idea that the films of The Archers were ‘produced, directed and written’ by two individuals. Powell was, after all, the more voluble character and the one who did the work on the floor. And didn’t Powell complain that Pressburger wasn’t really a film-maker, saying that ‘even with a writer as clever and subtle as Emeric, I always had this continual battle with words.’ But then commercial film-making isn’t about visual poetry, it’s about resolving the tension between the ‘literary’ and the visual aspects of any film. And while the task of directing a film starts with discussions on the first draft of a script, the act of writing it doesn’t end until the final cut has come out of the dubbing theatre. Therefore, it means something when a writer and director take equal responsibility for a finished film.

‘The screenwriter,’ says Mark Peploe, ‘should go on working on the film after the screenplay is finished, so as to keep the dialectic going with the director.’ It would take an enormous shift in the perception of what writers do before producers would pay for them to be on a film up to the final cut, or directors tolerate their presence and interventions, but it’s that sort of recognition of the writer’s importance that is required. It was the forceful presence of the writer that accounted for such 1940s masterpieces as Brief Encounter , The Third Man or A Canterbury Tale , with their rhythmic structures, themes skillfully woven through the picture, echoes and resonances capturing the viewer in a sense of mystery and excitement.

Even with the more ambitious recent scripts from British writers, such as Mick Eaton’s Fellow Traveller or Mark Peploe’s The Last Emperor , one feels that their innovations were not followed through. With The Last Emperor , it is the grandeur of the decor and the mise en scene that prevents the connections made in Peploe’s script from becoming fully apparent.

The writer has to gain the director's trust. That requires a lot of patience, a lot of toughness. You have to be able to rewrite things time and time again. You have to come out of it at the other end and not break down. So you really have to get his trust. But with some directors you're not going to get it and there's nothing you can do. TROY KENNEDY MARTIN (Edge of Darkness, Troppo)

I feel a chill of fear sometimes when I watch American films, thinking how much work has gone into the script. Film is about taking millions and millions of permutations on what a character can do and trying to get a ballpark of the best 20. When the ending works, you know that it has probably been done 70 times. DAVID PIRIE (Rainy Day Women, Never Come Back)

Bertolucci has an astonishing eye for landscape and sense of scene construction, but it’s significant that The Conformist acquired its shape in the editing room by Franco Arcalli, and none of his subsequent films has matched it for structural complexity. At the writing stage of The Last Emperor, Bertolucci initially dismissed the idea of using flashback, saying that it was old-fashioned. ‘I had,’ says Peploe, ‘to spend a very hard two months, taking out the flashback, doing it straight, and I almost went mad. I couldn’t do it.’ Eventually Peploe got his way, but had there been more balance between writer and director, the film could arguably have been a much more exciting journey into its central character’s psyche.

Producers have the responsibility for determining how writers and directors work together. They lay down the initial terms of their collaboration. They can resolve blockages that arise during the development process and keep writer and director from being carried away into self-indulgence, losing touch with the narrative and what the film should be saying to the audience. They can ensure that the writer is not being over-protective, or the director over-assertive. And they can encourage writer and director to keep on working until the script really has realised its potential. ‘Producers,’ says William Nicholson, ‘should not be shy and say my only job is to raise the money and put you two geniuses together. The producer too should have views and care about the structure.’

But if producers are too often careless of these responsibilities, it’s because the problems of raising finance are so overwhelming, and can come to dominate the project. ‘There are respectable producers,’ remarks Don Ranvaud of the European Script Fund, ‘who would settle for an insufficient script, even one that doesn’t make sense, so long as it pleases the actor or the financier they’re trying to hook. And if that guy wants something changed, then they’ll change it.’

For the production company, development is all money out, with no prospect of a return until the film is under way. Therefore those companies without access to a significant capital fund, which is most of them, will always be under pressure to get a film before the cameras. And where cash is available to finance the picture—thanks to the star, the director’s reputation or the quality of the concept—no one is going to turn it down because the script isn’t ready; the package could too easily fall apart, with the us distributor going bankrupt or the equity financiers suddenly finding they’re not as rich as they were.

But if they don’t get the script right, then British producers are never going to make films that strike chords with audiences around the world. It’s a problem they are going to have to resolve—by developing a steadier nerve, holding on until they know a script is ready, and only then allowing anyone to call ‘Action’. They have to take the long view, believing sufficiently in a film’s potential for success to be confident that, if they can only work through to a good script, they’ll be able to establish their finances on a more secure base.

For it’s only by developing scripts that tap the fears and longings of their characters, and tell stories that lock into deep human emotions, that producers will resolve the creative and economic problems confronting British cinema. British films may have been too often constricted by realism, or inappropriately wordy, or afflicted by theatrical performances, but these flaws aren’t simply rooted in the national culture. They reflect a refusal to appreciate how much it takes to develop a strong script. If British movies are ever going to be passionate, meaningful experiences, rather than flaccid records of historical events or half-hearted imitations of American genres, then producers will have to learn how to get writers and directors working together.

Great analysis Daniel. I just love this"Flannery O’Connor’s sharp remarks on creative writing courses: ‘Everywhere I go I’m asked if I think universities stifle writers. My opinion is that they don’t stifle enough of them.’ "