Before there was 'Dune', there were 'The Godmakers'

Frank Herbert is best known for the epic 'Dune' world he created with a total of six novels. Dune came to life in the sixties, and its success gave new life to some of Herbert's earlier materials.

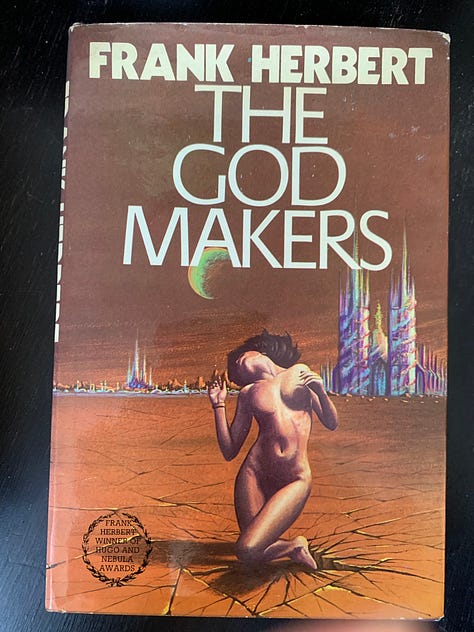

I recently picked up a worn sci-fi novel paperback with a fairly intriguing cover and title - ‘The Godmakers’ … and only then saw that it was a novel by Frank Herbert, he who has given the world the world of Dune (to this day, I think, the best-selling sci-fi novel of all time).

I’ll start by admitting that I’ve never read any of the Dune novels. I knew that particular world only because of the 1984 David Lynch-helmed film that was, well, an eighties-fest to be sure - should you ever wish to experience the eighties, watch that original Dune film!

Now these days Dune most certainly is in vogue again with the Denis Villeneuve films and thus a whole new generation gets to discover Frank Herbert’s very, very prolific, fertile and inventive mind.

Back to The Godmakers: A quirky tale, vast in scope, yet up close and personal. Just a few characters and yes, the protagonist will become a god. I enjoyed the story, but it sure felt like reading a series of cobbled-together short stories. Turns out, that’s just what this novel is. One might assume that, when Dune became a success in the sixties, the giddy publisher asked Herbert, “So what else you got for me? How about you take some of those short stories and weave them into one novel. How about it, Herb?”

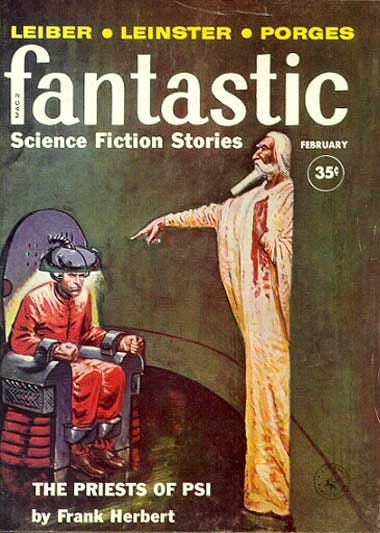

Well, Herb delivered. He took four short stories written before Dune - ‘You Take the High Road (1958); ‘Missing Link’ (1959); ‘Operation Haystack’ (1959); and ‘The Priests of Psi’ (1960) - and reworked them into ‘The Godmakers’, published in 1972. I’ve no doubt that any Dune fan will be interested in reading this, because clearly some of the Dune groundwork was laid down in Herbert’s earlier stories.

‘The Godmakers’ is a short novel and packed with short chapters and philosophical introductions to every chapter. It moves at a good pace, but as said feels cobbled at times, a bit choppy here and there. There’s some good dialogue, especially the back and forth between protagonist Lewis Orne and his snarky superior Stetson. The choppiness has to do not just with the episodic occurrences, but also with the shifting to the ‘Godmaker’ planet and the philosophical notes interspersed with every chapter. Those are intriguing, but they definitely stop the flow of the story every time. Here’s one:

“To become a god, a living creature must transcend the physical. The three steps of this transcendent path are known. First, he must come upon the awareness of secret aggression. Second, he must come upon the discernment of purpose within the animal shape. Third, he must experience death. When this is done, the nascent god must find his own rebirth in a unique ordeal by which he discovers the one who summoned him.” (The Making of a God - The Amel Handbook)

Key to the story is the notion that gods are not born, that they are made. Gods and religions are made by us, Herbert tells us in this novel. And there’s a great universal power calls Psi, which can be harnessed by the enlightened ones on the Godmaker planet of Amel. In this novel, same as in Dune, Herbert spends a good deal of time focusing on the topic of religion - and I like how he goes about it. Here a few examples of his use of quotes in the novel:

“Anyone who has ever felt his skin crawl with the electrifying awareness of an unseen presence knows the primary sensation of Psi.” (Halmyrach, Abbod of Amel - Psi and Religion, Preface)

“Because the earliest Psi sensations came upon mankind from the unknown, primitive emotional associations with Psi were those of fear and the maya projection of false realities, of incubi and witches and warlocks and sabbats. These associations are bred into us and our kind has a strong tendency to recapitulate the old mistakes.” (Halmyrach, Abbod of Amel - Psi and Religion)

As you can see, he beautifully builds on our world and history of religions and extrapolates toward something more enlightened as lived by the wise ones of the future. I have to admit, I would have liked to see Herbert’s book shelves - no doubt it was packed with books on psychology, philosophy and the history and inner workings of religions across the globe.

“Those who seek knowledge for the sake of reward, yea even to the knowledge of Psi, repeat the errors of the primitive religions. Knowledge gained out of fear or hope of reward holds you in a basket of ignorance. Thus the ancients learned to falsify their lives.” (Sayings of the Abbods - The Approach to Psi)

In the end, when Orne has become a god, he leaves a note for the Abbod and ends it with a humorous note about what he wants inscribed on his tombstone:

“He chose infinity, one finite step at a time.”

Nice, right? Something we might all take to heart. To be there, 100%, for every moment that is our life. And in those moments, we have - we are - infinity.